How to Recycle Plastics

Contents

- 1 Recycling Plastics

- 1.1 Plastics - what are they and how do they behave?

- 1.2 Why recycle plastics?

- 1.3 Products from plastic

- 1.4 References and further reading

- 1.5 Useful addresses

- 1.6 Categories

Recycling Plastics

Plastics - what are they and how do they behave?

Plastics are organic polymeric materials consisting of giant organic molecules. Plastic materials can be formed into shapes by one of a variety of processes, such as extrusion, moulding, casting or spinning. Modern plastics (or polymers) possess a number of extremely desirable characteristics; high strength to weight ratio, excellent thermal properties, electrical insulation, resistance to acids, alkalis and solvents, to name but a few.

These polymers are made of a series of repeating units known as monomers. The structure and degree of polymerisation of a given polymer determine its characteristics. Linear polymers (a single linear chain of monomers) and branched polymers (linear with side chains) are thermoplastic, that is they soften when heated. Cross-linked polymers (two or more chains joined by side chains) are thermosetting, that is, they harden when heated.

Thermoplastics make up 80% of the plastics produced today. Examples of thermoplastics include;

• high density polyethylene (HDPE) used in piping, automotive fuel tanks, bottles, toys,

• low density polyethylene (LDPE) used in plastic bags, cling film, flexible containers;

• polyethylene terephthalate (PET) used in bottles, carpets and food packaging;

• polypropylene (PP) used in food containers, battery cases, bottle crates, automotive parts and fibres;

• polystyrene (PS) used in dairy product containers, tape cassettes, cups and plates;

• polyvinyl chloride (PVC) used in window frames, flooring, bottles, packaging film, cable insulation, credit cards and medical products.

There are hundreds of types of thermoplastic polymer, and new variations are regularly being developed. In developing countries the number of plastics in common use, however, tends to be much lower.

Thermosets make up the remaining 20% of plastics produced. They are hardened by curing and cannot be re-melted or re-moulded and are therefore difficult to recycle. They are sometimes ground and used as a filler material. They include: polyurethane (PU) - coatings, finishes, gears, diaphragms, cushions, mattresses and car seats; epoxy - adhesives, sports equipment, electrical and automotive equipment; phenolics - ovens, handles for cutlery, automotive parts and circuit boards (The World Resource Foundation).

Nowadays, the raw materials for plastics come mainly from petrochemicals, although originally plastics were derived from cellulose, the basic material of all plant life.

Why recycle plastics?

In ‘western’ countries, plastic consumption has grown at a tremendous rate over the past two or three decades. In the ‘consumer’ societies of Europe and America, scarce petroleum resources are used for producing an enormous variety of plastics for an even wider variety of products. Many of the applications are for products with a life-cycle of less than one year and then the vast majority of these plastics are then discarded. In most instances reclamation of this plastic waste is simply not economically viable.

In industry (the automotive industry for example) there is a growing move towards reuse and reprocessing of plastics for economic, as well as environmental reasons, with many praiseworthy examples of companies developing technologies and strategies for recycling of plastics.

Not only is plastic made from a non-renewable resource, but it is generally non-biodegradable (or the biodegradation process is very slow). This means that plastic litter is often the most objectionable kind of litter and will be visible for weeks or months, and waste will sit in landfill sites for years without degrading.

Plastic litter poses further serious health and ecological issues:

- Offers breeding places for the mosquitos that are the carrying dengue and malaria.

- Is being eaten by cattle and wild animals and endangers their lives,

- Where it lays, it stops vegetation from growing,

- Washed down by rain it obstructs drains and pipings causing floodings,

- Washed down along rivers, it ends in the sea where birds and fishes eat it, or it is torn apart in thousands of small pieces and slowly released chemicals in the water.

|

Plastics fact file

|

Although there is also a rapid growth in plastics consumption in the developing world, plastics consumption per capita in developing countries is much lower than in the industrialised countries. These plastics are, however, often produced from expensive imported raw materials. There is a much wider scope for recycling in developing countries due to several factors:

- Labour costs are lower.

- In many countries there is an existing culture of reuse and recycling, with the associated system of collection, sorting, cleaning and reuse of ‘waste’ or *There is often an ‘informal sector’ which is ideally suited to taking on small-scale recycling activities. Such opportunities to earn a small income are rarely missed by members of the urban poor.

- There are fewer laws to control the standards of recycled materials. (This is not to say that standards can be low - the consumer will always demand a certain level of quality).

- Transportation costs are often lower, with hand or ox carts often being used.

- Low cost raw materials give an edge in the competitive manufacturing world.

- Innovative use of scrap machinery often leads to low entry costs for processing or manufacture.

In developing countries the scope for recycling of plastics is growing as the amount of plastic being consumed increases.

Plastics for recycling

Not all plastics are recyclable. There are 4 types of plastic which are commonly recycled:

- Polyethylene (PE) - both high density and low-density polyethylene.

- Polypropylene (PP)

- Polystyrene (PS)

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

A common problem with recycling plastics is that plastics are often made up of more than one kind of polymer or there may be some sort of fibre added to the plastic (a composite) to give added strength. This can make recovery difficult.

Sources of waste plastics

Industrial waste (or primary waste) can often be obtained from the large plastics processing, manufacturing and packaging industries. Rejected or waste material usually has good characteristics for recycling and will be clean. Although the quantity of material available is sometimes small, the quantities tend to be growing as consumption, and therefore production, increases.

Commercial waste is often available from workshops, craftsmen, shops, supermarkets and wholesalers. A lot of the plastics available from these sources will be PE, often contaminated.

Agricultural waste can be obtained from farms and nursery gardens outside the urban areas. This is usually in the form of packaging (plastic containers or sheets) or construction materials (irrigation or hosepipes).

Figure 2: Mixed waste plastic requiring sorting before it can be recycled. ©World Resource Foundation

Municipal waste can be collected from residential areas (domestic or household waste), streets, parks, collection depots and waste dumps. In Asian cities this type of waste is common and can either be collected from the streets or can be collected from households by arrangement with the householders. (Lardinois 1995)

Identification of different types of plastics

There are several simple tests that can be used to distinguish between the common types of polymers so that they may be separated for processing.

The water test. After adding a few drops of liquid detergent to some water put in a small piece of plastic and see if it floats.

Burning test. Hold a piece of the plastic in a tweezers or on the back of a knife and apply a flame. Dose the plastic burn? If so, what colour?

Fingernail test. Can a sample of the plastic be scratched with a fingernail?

|

Test |

PE |

PP |

PS |

PVC* |

|

Water |

Floats |

Floats |

Sinks |

Sinks |

|

Burning |

Blue flame with yellow tip, melts and drips. |

Yellow flame with blue base. |

Yellow, sooty flame - drips. |

Yellow, sooty smoke. Does not continue to burn if flame is removed |

|

Smell after burning |

Like candle wax. |

Like candle wax - less strong than PE |

Sweet |

Hydrochloric acid |

|

Scratch |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

*To confirm PVC, touch the sample with a red-hot piece of copper wire and then hold the wire to the flame. A green flame from the presence of chlorine confirms that it is PVC.

Source: Vogler. 1984

To determine if a plastic is a thermoplastic or a thermoset, take a piece of wire just below red heat and press it into the material. If the wire penetrates the material, it is a thermoplastic; if it does not it is a thermoset.

A coding system has also been introduced in the United States to aid identification of plastics for reclamation. It is based on the ‘Recycle Triangle’ with a series of numbers and letters to help with identification. More information is available from the Association of Plastic Manufacturers in Europe (APME). See useful addresses section later in this brief.

Collection

When thinking about setting up a small-scale recycling enterprise, it is advisable to first carry out a survey to ascertain the types of plastics available for collection, the type of plastics used by manufacturers (who will be willing to buy the reclaimed material), and the economic viability of collection.

The method of collection can vary. The following gives some ideas;

- House to house collection of plastics and other materials (e.g. paper).

- House to house collection of plastics only (but all types of polymer).

- House to house collection of certain objects only.

- Collection at a central point e.g. market or church.

- Collection from street boys in return for payment.

- Regular collection from shops, hotels, factories, etc.

- Purchase from scavengers on the municipal dump.

*Scavenging or collecting oneself.

The method will depend upon the scale of the operation, the capital available for set-up, transport availability, etc.

Processing of reclaimed plastic - processes and technology for small-scale recycling enterprises

Initial upgrading.

Once the plastic has been collected, it will have to be cleaned and sorted. The techniques used will depend on the scale of the operation and the type of waste collected, but at the simplest level will involve hand washing and sorting of the plastic into the required groups. More sophisticated mechanical washers and solar drying can be used for larger operations. Sorting of plastics can be by polymer type (thermoset or thermoplastic for example), by product (bottles, plastic sheeting, etc.), by colour, etc.

Figure 3: Collection of Waste Materials. © World Resource Foundation

Figure 4: Flow chart of a typical waste plastic reprocessing stream in a low-income country (TOOL 1995)

Size reduction techniques

Size reduction is required for several reasons; to reduce larger plastic waste to a size manageable for small machines, to make the material denser for storage and transportation, or to produce a product which is suitable for further processing. There are several techniques commonly used for size reduction of plastics;

Cutting

is usually carried out for initial size reduction of large objects. It can be carried out with scissors, shears, saw, etc.

Shredding

is suitable for smaller pieces. A typical shredder has a series of rotating blades driven by an electric motor, some form of grid for size grading and a collection bin. Materials are fed into the shredder via a hopper which is sited above the blade rotor. The product of shredding is a pile of coarse irregularly shaped plastic flakes which can then be further processed.

Agglomeration

is the process of pre-plasticising soft plastic by heating, rapid cooling to solidify the material and finally cutting into small pieces. This is usually carried out in a single machine. The product is coarse, irregular grain, often called crumbs.

Further processing techniques

Extrusion and pelletising

The process of extrusion is employed to homogenise the reclaimed polymer and produce a material that it subsequently easy to work. The reclaimed polymer pieces are fed into the extruder, are heated to induce plastic behaviour and then forced through a die (see the following section on manufacturing techniques) to form a plastic spaghetti which can then be cooled in a water bath before being pelletised. The pelletisation process is used to reduce the ‘spaghetti’ to pellets which can then be used for the manufacture of new products.

Manufacturing techniques

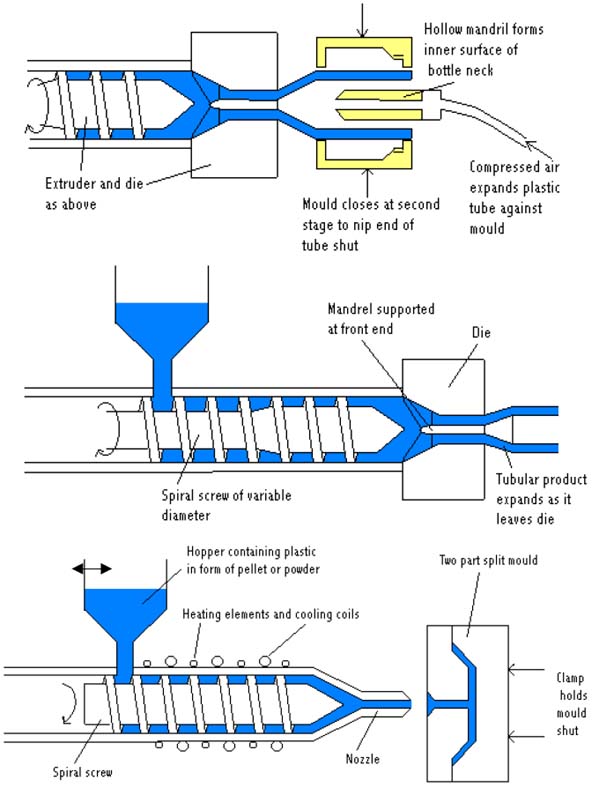

Extrusion

The extrusion process used for manufacturing new products is similar to that outlined above for the process preceding pelletisation, except that the product is usually in the form of a continuous ‘tube’ of plastic such as piping or hose. The main components of the extrusion machine are shown in Fig. 2 below. The reclaimed plastic is forced along the heated tube by an archimedes screw and the plastic polymer is shaped around a die. The die is designed to give the required dimensions to the product and can be interchanged.

Injection moulding

The first stage of this manufacturing process is identical to that of extrusion, but then the plastic polymer emerges through a nozzle into a split mould. The quantity of polymer being forced out is carefully controlled, usually by moving the screw forward in the heated barrel. A series of moulds would be used to allow continual production while cooling takes place. See Figure 2 below. This type of production technique is used to produce moulded products such as plates, bowls, buckets, etc.

Blow moulding

Again the spiral screw forces the plasticised polymer through a die. A short piece of tube, or ‘parison’ is then enclosed between a split die -which is the final shape of the product - and compressed air is used to expand the parison until it fills the mould and achieves its required shape. This manufacturing technique is used for manufacturing closed vessels such as bottles and other containers. See Figure 2 below.

Film blowing

Film blowing is a process used to manufacture such items as garbage bags. It is a technically more complex process than the others described in this brief and requires high quality raw material input. The process involves blowing compressed air into a thin tube of polymer to expand it to the point where it becomes a thin film tube. One end can then be sealed and the bag or sack is formed. Sheet plastic can also be manufactured using a variation of the process described.

Figure 5: Plastic manufacturing techniques; extrusion (top), blow moulding (middle) and injection moulding (bottom).

Products from plastic

There is an almost limitless range of products that can be produced from plastic. However, the market for recycled plastic products is limited due to the inconsistency of the raw material. Many manufacturers will only incorporate small quantities of well-sorted recycled material in their products whereas others may use a much higher percentage of recycled polymers. Much depends on the quality required.

In developing countries, where standards are often lower and raw materials very expensive, there is a wider scope for use of recycled plastic material. The range of products varies from building materials to shoes, kitchen utensils to office equipment, sewage pipe to beauty aids.

Manufacturers of plastics recycling equipment

Machinery for plastics recycling and processing varies in size and sophistication. In most developing countries it is not possible to find new equipment which can be purchased off-the-shelf and machinery will either have to be imported, manufactured locally, or improvised. Within the informal sector, the latter is usually the most common method of procuring equipment and the level of improvisation is often admirable and ingenious.

Below are the addresses if some manufacturers and suppliers of plastics recycling equipment (for a more comprehensive list see Vogler [1]):

|

Brimco Plastic Machinery Prt. Ltd. |

Plasplant Machinery Ltd. |

|

Produce general equipment for plastics manufacture. |

Suppliers of used and new equipment for plastics recycling. Many years experience of supplying to developing countries. |

References and further reading

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Recycling Plastics.

To look at the original document follow this link: http://www.practicalaction.org/?id=technical_briefs_manufacturing

1. Vogler, Jon, Small-scale recycling of plastics. Intermediate Technology Publications 1984. A book aimed at small-scale plastics recycling in developing countries.

2. Vogler, Jon, Work from Waste. Intermediate Technology Publications 1981. A classic text for those recycling wastes to create employment.

3. Lardinois, I., and van de Klundert, A., Plastic Waste, Option for small-scale resource recovery. TOOL 1995. A publication in the urban solid waste series. Gives many examples of successful plastics recycling operations in developing countries.

4. Birley, A. W., Heath, R. J., and Scott, M. J. Plastics Materials. Blackie, 2nd ed. 1988. Introductory scientific textbook.

5. Harper, Charles A., and others, etc. Handbook of Plastics and Elastomers. McGraw-Hill, 1975. Basic data on design, construction and use.

6. Roth, Laszlo. A Basic Guide to Plastics for Designers, Technicians, and Crafts People. Prentice-Hall, 1985. Introduction to materials and technology.

7. Sparke, Penny, ed. The Plastics Age: from Modernity to Post-Modernity. Victoria and Albert Museum, 1990. A celebration of the usefulness and aesthetics of plastics; well illustrated.

8. "Plastics," Microsoft® Encarta® 98 Encyclopedia. © 1993-1997 Microsoft Corporation. Encyclopedia article.

</div>

Useful addresses

World Resource Foundation

Heath House

133 High Street, Tonbridge

Kent TN9 1DH

Tel +44 ( 0)1732 368333

Fax +44 (0)1732 368337

http://www.wrf.org.uk

The Warmer Bulletin' published 4 times a year (subscription required)

WASTE Nieuwehaven 201,

2801 VW Gouda, The Netherlands.

Tel: +31 (0)182 522 625

Fax: +31 (0)182 550313

Consultants in Urban waste management in developing countries.

UNDP / World Bank

Integrated Resource Recovery Programme,

1818 H. Street NW, Washington DC, USA.

Tel: +1 (202) 477 1254

Fax: +1 (202) 477 1052

Publications on policy and case studies

TNO Plastics and Rubber Research Inst.

PO Box 6031, 2600 JA Delft,

The Netherlands.

Tel: +31 (15) 69 66 21

Fax: +31 (15) 56 63 08

Research into plastics and rubber, advice and training.

RAPRA Technology Ltd.

Shawbury, Shrewsbury,

Shropshire SY4 4NR

Tel: +44 (0)1939 250 383

Fax: +44 (0)1939 251 118

Website: http://www.rapra.net

Technical info centre for rubbers and plastics, consulting and analysis services.

Publish Journal Progress in Rubber and Plastics technology and a publications catalogue

European Centre for Plastics in the Environment and Association of Plastics Manufacturers in Europe,(APME),

Avenue E. van Nieuwenhuyse 4, BP3,

B-1160 Brussels, Belgium

Tel: +32 (2) 675 32 97

Fax: +32 (2) 675 39 35

General info on plastics waste recycling

Plastics Recycling Foundation,

1275 K Street NW, Suite 400,

Washington DC 20005, USA.

Tel: +1 (202) 371 5337

Sponsor R&D, Info on technology and markets.

Appropriate Technology Development Association,

PO Box 311, Gandhi Bhawan,

Lucknow-226001, U.P.

India.

Research Institute - rubber and plastics

Environmental Development Action in the Third World,

Head Office: PO Box 3370, Dakar, Senegal.

Tel: +221 (22) 42 29 / 21 60 27

Fax: +221 (22) 26 95

Regional offices in Colombia, Bolivia and Zimbabwe. Database, library, publications and advice. Quarterly magazine 'African Environment'

CAPS

Room 8, Maya Building, 678 EDSA, Cubao,

Quezon City, Metro Manila,

The Philippines.

Contact: Mr. Dan Lapid

Tel: +63 (2) 912 36 08

Fax: +63 (2) 912 34 79

Consultants with on-line enquiries, training, info and education.

Internet addresses

http://www.polymers.com/dotcom/home.html

This is the polymers and plastics industry site which contains an online magazine, links to tutorials and chemistry guides, and links to related sites. Registration is required.

Practical Action, The Schumacher Centre For Technology & Development

Bourton Hall, Bourton-on-Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire CV23 9QZ, UK

Tel: + 44(0) 1926 634400 Fax: +44(0) 1926 634401

E-mail: Infoserv@practicalaction.org.uk Web: http://www.practicalaction.org

Intermediate Technology Development Group Ltd

Patron HRH - The Prince of Wales, KG, KT, GCB

Company Reg. No 871954, England Reg. Charity No 247257 VAT No 241 5154 92

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail:practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk

web:www.practicalaction.org

Categories

- Community

- Energy

- Equipment Design

- Hygiene

- Ideas

- Mechanics

- Pest control

- Pollution

- Prevention

- Products

- Recycling

- Resource Management

- Sanitation

- Waste

- Difficult

- High Technology

- Global Technology

- Arid Climate

- Forest Environment

- Global

- Mediterranean Climate

- Monsoon Climate

- Montaneous Environment

- Coastal Area

- Lakes and Rivers

- Rural Environment

- Temperate Climate

- Tropical Climate

- Urban Environment

- Plastic container

- One Person and more

- Household

- Village

- Neighbourhood

- Application

- Practical Action

- Requested translation to Spanish

- Requested translation to Arabic