Difference between revisions of "What to Do with Ginger"

(→How to make a Ginger Drink) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ==How to make a Ginger Drink | + | =How to Process Ginger= |

| + | {{:How to Process Ginger}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | =How to Produce Essential oils= | ||

| + | {{:How to Produce Essential Oils}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | =How to make a Ginger Drink= | ||

{{:Ginger drink}} | {{:Ginger drink}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Requested translation to Spanish]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:05, 30 August 2012

Contents

- 1 How to Process Ginger

- 1.1 Short Description

- 1.2 Fresh ginger

- 1.3 Preserved ginger

- 1.4 Dried ginger

- 1.5 Processing ginger

- 1.6 Making dried ginger

- 1.7 Quality of dried ginger

- 1.8 Quality of the final product is determined by both pre-harvest and post-harvest factors

- 1.9 Ginger oil distillation

- 1.10 References and further reading

- 1.11 Useful addresses

- 1.12 Related Articles

- 2 How to Produce Essential oils

- 3 Essential Oils

- 4 How to make a Ginger Drink

How to Process Ginger

Short Description

- Problem:

- Idea:

- Difficulty:

- Price Range:

- Material Needeed:

- Geographic Area:

- Competencies:

- How Many people?

- How Long does it take?

Ginger is an upright tropical plant (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) that grows to about 1 metre tall. Ginger is obtained from the rhizomes of the plant Zin giber officinale Roso. It originated in South East Asia and is valued for the dried ginger spice and preserved crystallised ginger.

Before processing ginger, it is recommended that a market survey is carried out. This will include information on the availability of raw material, availability of processing materials and equipment, access to markets and demand for the different ginger products. This information should indicate whether your business is likely to succeed.

Ginger is usually available in three different forms;

- fresh (green) ginger

- preserved ginger in brine or syrup

- dried ginger spice

Fresh ginger

Fresh is usually only eaten in the area where it is produced although it is possible to transport fresh roots internationally. Both mature and immature rhizomes are consumed as a fresh vegetable.

Preserved ginger

Preserved ginger is only made from the immature rhizomes. Most preserved ginger is exported. Hong Kong, China and Australia are the major producers of preserved ginger and dominate the world market.

Making preserved ginger is not simple, it requires a lot of care and attention to quality, only the youngest, most tender stems of ginger should be used. It is difficult to compete with the well established Chinese and Australian producers. This technical brief will only describe the production of dried ginger.

Dried ginger

Dried ginger spice is produced from the mature rhizome. As the rhizome matures the flavour and aroma become much stronger. Dried ginger is exported, usually in large pieces which are then ground into a spice in the country where it is used. Dried ginger can be ground and used directly as a spice and also for the extraction of ginger oil and ginger oleoresin.

Processing ginger

There are two important factors to consider when selecting ginger rhizomes for processing;

- the stage of maturity at harvest:

Ginger rhizomes may be harvested from about 5 months after planting. At this age, they are immature. They are tender with a mild flavour and are suitable for fresh consumption or for processing into preserved ginger. After 7 months the rhizomes will become less tender and the flavour will be too strong to use them fresh. They are then only useful for drying. Mature rhizomes for drying are harvested between 8 and 9 months of age when they have a high aroma and flavour. If they are harvested later than this, the fibre content will be to high.

- native properties of the type grown.:

Gingers grown in different parts of the world can differ in their native properties such as taste, flavour, aroma and colour. This affects their suitability for processing. It is most important when preparing dried ginger which needs rhizomes with a strong flavour and aroma. When drying ginger, size is also important. Medium sized rhizomes are the most suitable for drying. The large rhizomes often have a high moisture content which causes problems with drying.

Making dried ginger

Dried ginger is available in many forms. The rhizomes may be left whole or they may be split or sliced into smaller pieces to accelerate drying. Sometimes the rhizomes are killed by peeling or boiling them for 10-15 minutes. This results in a black product which can be bleached using lime or a sulphurous acid. The only product which is acceptable for the UK market is cleanly peeled dried ginger.

Dried ginger is produced according to the following steps;

- The fresh rhizome is harvested at between 8 and 9 months of age.

- The roots and leaves are removed and the rhizomes are washed.

- The rhizome is killed. This is done by peeling, rough scraping or chopping the rhizome into slices (either lengthwise or across the rhizome). Whole, unpeeled rhizomes can be killed by boiling in water for about 10 minutes.

- The rhizome pieces are then dried. This is often by sun-drying. Information on drying foods is included in a separate technical brief.

Quality of dried ginger

The most important factors to control in the production of dried ginger are:

- The appearance of the final product - especially for whole roots for export (not so important if the product is to be ground or used for oil extraction) Content of volatile oil and fibre - especially for extraction of oils

- Level of pungency - especially for the extraction of oils

- Aroma and flavour - especially for the extraction of oils

Quality of the final product is determined by both pre-harvest and post-harvest factors

- The most important factor is the cultivar of ginger grown. This determines the flavour, aroma, pungency and levels of essential oil and fibre.

- The stage of maturity of the rhizome at harvest determines its end use. At 8-9 months of age rhizomes are most suitable for drying.

- When the rhizomes are harvested they should be handled with care to prevent injury. They should be washed immediately after harvest to obtain a pale colour. The wet rhizomes should not be allowed to lie too long in heaps as they are liable to ferment.

- Care should be taken when removing the outer cork skin. It is essential to remove the skin to reduce the fibre content, but if the peeling is too thick, it may reduce the content of volatile oil which is contained near the surface.

- During drying, the rhizomes lose about 60-70% of their weight and achieve a moisture content of 7-12%. Care should be taken to prevent the growth of mould.

- Dried ginger should be stored in a dry place to prevent the growth of mould. Storage for a long time results in the loss of flavour and pungency.

|

Processing dried ginger |

Quality control |

|

Take care to prevent injury and bruising |

. |

|

Harvest ginger at 8-9 months of age |

<8-9 months flavour not developed >8-9 months becomes too fibrous |

|

Remove the roots and leaves. Wash the rhizomes |

Wash immediately to get a pale colour. Do not leave wet rhizomas in heaps for long periods as they will ferment. |

|

Kill the rhizome by one of the methods:

|

Take care to only remove the fibrous outer cork skin. If peeling is too thick, essential oil and flavour will be lost. Boiling results in a black colour which requires bleaching |

|

Dry to moisture content of 7-12% Store in a cool dry place. |

Dry Rapidly to prevent growth. Do not store for long periods as flavour will be lost |

Ginger oil distillation

Ginger oil is the essential oil obtained by steam distillation of the dried spice. The essential oil possesses the aroma and flavour of the spice but lacks the characteristic pungency. It finds its main application in the flavouring of beverages but it is also used in confectionery and perfumery. Distillation of the oil is mainly carried out in the major market areas of North America and Western Europe using imported dried ginger. However, ginger oil is produced for export in some of the spice growing countries, notably China, India, Indonesia, Australia and Jamaica.

References and further reading

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Ginger Processing.

To look at the original document follow this link: http://www.practicalaction.org/?id=technical_briefs_food_processing

Ginger: Sri Lankan Aromatic Plants of Economic Value Booklet No 7, Nirmala Pieris, Ceylon Institute of Scientific & Industrial Research (CISIR), 1982

A note on ginger oil distillation, ITDG Report, 1979

Useful addresses

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail:practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk web:www.practicalaction.org

ITI (CISIR is now called the Industrial Technology Institute (ITI))

Industrial Technology Institute

363, Bauddhaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka

Telephone : +94-11-2693807/9, +94-11-2698621/3

Fax : +94-11-2686567

Email : info@iti.lk

Website: http://iti.lk/

Related Articles

- How to Produce Essential Oils

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Process Spice

- How to Process Turmeric

- How to Process Ginger

- How to Process Cumin

- How to Process Cinnamon

- How to Process Pepper

- How to Process Nutmeg and Mace

- What to Do with Vetiver

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

How to Produce Essential oils

Essential Oils

Short Description

- Problem: Extraction of oils from various plants, fruits for main uses of fragrance, paint etc.

- Information Type: Application

- Difficulty: Medium

- How Many people? Up to five people

Small-scale production

Essential oils are steam-volatile oils distilled from plant materials and represent the typical flavour and aroma of a particular plant. They are found in flowers, leaves, roots, seeds and barks and find use principally in perfumery and flavourings. The essential oil content of plant material is low, typically 1 to 3% of the plant weight. They are thus low-volume, very high value products. This makes them attractive crops for remote smallholders where high transport costs prevent the transport of lower value cash crops.

Essential oils contain a complex mix of components and it is this mix that gives the “note” that experts recognise. Table 1 shows the important constituents of some common essential oils.

Table 1 - Essential oils

|

Name |

Part of plant used |

Botanical Name |

Important Constituents |

Uses |

|

Lemongrass and |

Leaf |

Cymbopogon spp |

Citral |

Perfumery |

|

Eucalyptus |

Leaf |

Eucalyptus globulus |

Cineale |

. |

|

Cinnamon leaf |

Leaf |

Cinnamomum zeylanicum |

Eugenol |

Used to make artificial vanilla |

|

Clove |

Bud |

Eugenia caryophyllus |

Eugenol |

Dentistry |

|

Turpentine |

Pinus spp |

Terpenes |

Paints | |

|

Lavender |

Flower |

Lavendula intermedia |

Linalol |

Perfumery |

|

Sandalwood |

Wood |

Santalum album |

Sanatols |

Perfumery |

|

Nutmeg |

Nut |

Myristica fragrans |

Myristicin |

. |

|

Almond |

Nut |

Prunis communis |

Benzaldehyde |

. |

|

Coriander |

Seed |

Coriandrum sativum |

Linalol

|

. |

The quality of the oil obtained from a particular species will be influenced by where it is grown and how it has been processed. New producers are likely to meet with resistance from buyers as this is a very conservative market depending to a great extent on trust regarding supply and quality. Producers and buyers also closely guard information and “secrets”. Once established trading relationships are made, however, reliable markets can be gained.

Essential oils can be divided into two broad categories:

• Large volume oils which are usually distilled from leafy material such as lemon grass, citronella and cinnamon leaves. Lemon, lime and orange oils are also produced in very large amounts.

• Small volume oils which are usually distilled from fruits, seed, buds and, to a lesser extent, flowers, e.g. cloves, nutmeg ,coriander, vetiver and flower oils.

Harvesting

Correct harvesting is very important. The essential oil content varies considerably during the development of the plant and even the time of day. If the plant is harvested at the wrong time, the oil yield or its quality can be severely reduced.

Essential oils are usually contained in oil glands, or veins that are fragile. Poor handling will break these structures and release the oils resulting in losses. This is the reason a strong smell is given off when these plants are handled. Some examples of harvesting of common oils are:

• Citronella and lemongrass. The first harvest can take place 6-9 months after planting. Then the grass can then be harvested up to four times a year. If harvested too often, the productivity of the plant will be reduced and the plant may even die. If the plant is allowed to grow too large, the oil yield is reduced. For lemongrass it should be 1.2m high with 4-5 leaves. The grass should be harvested early in the morning as long as it is not raining. Harvesting can be done with machetes or simple knives.

• Cinnamon bark is harvested during the wet season since the rains facilitate the peeling of the bark. Harvesting involves the removal of bark from stems measuring 1.2-5 cm in diameter. This takes place early in the morning.

• Spices should be harvested correctly and at the correct stage of maturity. The main obstacle to correct harvesting is the crop being picked immature. This is usually due to fear of theft or the farmer requiring money urgently.

• Flowers such as ylang-ylang, should be picked very carefully and processed as soon as possible.

The preparation of the material for distillation varies. Some materials, and in particular flowers, should be distilled as quickly as possible. Many herbs are left to wilt, or are dried before distillation while barks, seeds and roots can be dried and stored for several months prior to distillation. Information on small scale drying systems can be found in the Practical Action Technical Briefs on drying.

As oil is lost during drying care needs to be taken and low temperatures used. Allowing leaves to dry in the shade or partial shade will result in less loss than direct sun drying. It is vital that the material is dried to a moisture content that is low enough to prevent the growth of moulds and typical moisture levels are shown in Table 2. The dried product should be stored in a cool place and protected from any pick-up of moisture.

Table 2: moisture contents for various spices

|

Spice |

Maximum final moisture |

|

Mace |

6.0 |

|

Nutmeg, cloves |

8.0 |

|

Turmeric, coriander |

9.0 |

|

Cinnamon |

11.0 |

|

Pepper, pimento, chillies, ginger |

12.0 |

|

Cardamom |

13.0 |

Distillation

This section examines the three common methods of distilling essential oils first examining the stills used and then condensers and oil separation methods.

• Water distillation is the simplest and cheapest distillation method. Two stills are shown in Figure 1 below.

The plant material is totally immersed in water and boiled. The steam and oil vapour is condensed and the oil is separated from the water using the system described below. The stills used are simple and find wide use amongst smallholder farmers, They are often heated over an open fire, which if not carefully controlled, may result in local overheating and burning of the charge. The quality of the oils produced in such traditional stills can be improved if they are heated by steam generated in a separate boiler. This, however, requires more expenditure in capital equipment. Water distillation remains the recommended method for barks, such as cinnamon and sandlewood, and certain flowers.

• Water-steam distillation is an improvement of simple water distillation. The charge of plant material is supported on a mesh or grill above boiling water as shown in Figure 2. The water is boiled, either over a fire or by steam from a boiler using a steam coil or jacket. This system greatly reduces local overheating and burning of the charge. It is important that the charge is packed evenly and not too tightly into the still. Over-packing will result in back-pressure and the steam finding channels through the charge leaving zones that have not been extracted.

• Steam distillation is the most advanced method and depends on live steam being supplied from an external boiler. The charge is again supported on a mesh above the base of the still and above a steam coil as shown in Figure 3.

The principle advantage of this method is that “dry steam” is used which results in reduced distillation times and hence greater outputs.

All still bodies should be insulated to reduce heat losses and fuel consumption. In some cases they are mounted on frames that allow them to be inverted in order to rapidly remove the hot charge after distillation. This reduces “turn round times” and increases daily outputs.

Modern still bodies are usually made from stainless steel while traditional systems use mild steel. For the reasons described below, in many cases, the use of expensive stainless steel is not necessary.

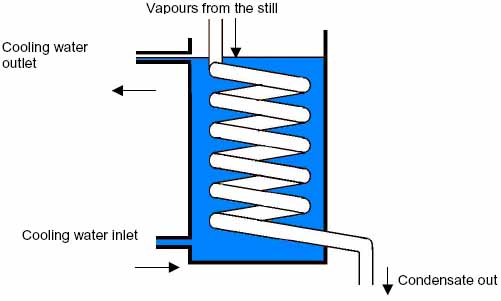

Condensers

Steam containing the essential oil vapour leaves the still via a head, known as a gooseneck, and passes to a condenser as shown in Figure 4. Simple condensers consist of a metal coil in a tank of flowing cold water. Ideally the coil of the condenser should be constructed from an inert material such as stainless steel in order to prevent the oil chemically reacting with mild steel. In many traditional stills the gooseneck and condenser coil were constructed from copper or brass that had been internally tinned to provide a reasonably inert surface. It is very important that the condensed steam (water) leaving the condenser is thoroughly cooled. If it is still warm there will be a loss of essential oil.

Oil separation

The final step in the distillation of essential oils is the separation from the water flowing from the condenser using a special flask called a Florentine. This is a very important stage as small quantities of oils of very high value are being handled and maximum efficiency is the key to profitability.

Most essential oils are lighter than water and float to the surface of the Florentine. Some oils, however, are denser than water and sink to the bottom. For this reason two types of Florentine are used as shown in Figure 5. It is common practice to link several Florentines together. Most of the oil will separate in the first flask but some will pass over with the water to the second, third etc. separates the oil from the water. This is usually done by letting the mixture settle in a large container made of glass. If the oil is heavier than water, the oil is collected from the bottom of the container, and if lighter from the top.

Using a sequence of oil separators will extract a greater amount of oil.

If the water is cloudy after separation, it should be returned to the distillation unit and redistilled. This is called 'cohabitation'.

At the end of the distillation the oil and water in the Florentines is placed in a large laboratory separating funnel (Figure 6) and allowed stand for several hours after which the water can be run off. At is stage a small plug of cotton wool is often placed in the outlet of the funnel. As the oil runs through the plug any final traces of water are removed.

The oil should be stored in brown glass bottles or drums, tightly closed and with the minimum possible headspace as oxygen in the air reacts with many oils.

References and further reading

Minor Oil Crops FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 94, B. Axtell, FAO,1992

Essential oil distillation Food chain No 24, ITDG, 1999

Quality Control of Essential Oils: Series on Aromatic Plants of Sri Lanka Booklet No 4,

Ceylon Institute of Scientific & Industrial Research (CISIR), 1981

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Essential Oils.

To look at the original document follow this link:

http://www.practicalaction.org/?id=technical_briefs_misc

Useful addresses

CISIR is now called the Industrial Technology Institute (ITI)

ITI

363 Bauddhaloka Mawatha

Colombia 7

Tel: +94 (1)698 624 /697 994

Fax: +94 (1) 698 624/697

E-mail: info@iti.lk

Website: http://www.iti.il

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail: practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk

web: www.practicalaction.org

Equipment suppliers

Please note this is a selective list of suppliers and does not imply endorsement by Practical Action.

Macanuda, Divisão de Máquinase Equipamantos

Rua Araranguá, 41

Bairro América - Joinville - SC

Brazil

Tel/Fax: +47 422 6706

E-mail: macanuda@ig.com.br

Website: http://www.macanuda.hpg.ig.com.br

Manufacture distillation equipment with capacities from 30 litres to 900 litres.

Newhouse Manufacturing Co., Inc.

1048 North Sixth Street

Redmond, OR 97756

USA

Tel: +1 541 548 1055,

E-mail: info@newhouse.mfg.com

John Dore & Co. Ltd

282 Chessington Road, Ewell

Epsom, Surrey, KT19 9XG

United Kingdom

Tel: + 44 (0)20 83931629

Fax: + 44 (0)20 87867627

Website: http://www.johndore.co.uk

John Dore & Co. Ltd supplies copper and stainless steel fabrications comprising: distillation plant for potable alcohol, essential oil stills, water stills, caramel pans, tanks and heat exchangers.

Sté de Fabrication Alambics Armagnacais et Charentais (SOFAC)

Z.I. Route de Nérac

32100 Condom

France

Tel: + 33 5 62 28 00 13

Fax: + 33 5 62 28 36 51

Manufacture distillation still for essential oils and alcohol.

Chemac Equipments PVT Ltd.

M.J.D'Souza Compound, Saphed Pool, Saki Naka, Mumbai - 400 072

India

Tel: +91 (0)22 2851 0777 / 859 2352.

Fax: +91 (0)22 2851 6986

Website: http://www.chemacequipments.com/

As an agency concerned with support to people in the developing countries, we do not in fact manufacture or sell equipment. Steam Distillation Units with a throughput of 50 litres up to 200

Alvan Blanch

Chelworth

Malmesbury

Wiltshire

SN16 9SG

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 666 577333

Fax: +44 (0) 666 577339

E-mail: info@alvanblanch.co.uk

Website: http://www.alvanblanch.co.uk

Essential Oil Distillation Plant used to extract oil from a variety of crops, herbs and spices using the method of distillation. Capacity: 130-420 kg/hour.

Related Articles

- How to Produce Essential Oils

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Process Spice

- How to Process Turmeric

- How to Process Ginger

- How to Process Cumin

- How to Process Cinnamon

- How to Process Pepper

- How to Process Nutmeg and Mace

- What to Do with Vetiver

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Categories

How to make a Ginger Drink

INGREDIENTS:

1 large ginger rhizome

6 cups water

1 oz sugar

2 oz lemon juice

PROCEDURE:

Peel 1 ginger rhizome.

Using clean food processor, chop it very fine in 1 C water.

Strain and return strained liquid to food processor.

Keep what’s left in strainer for cooking other food (frozen in ice-cube tray).

Add sugar, lemon juice and remainder of water in food processor.

Pour into clean bottle and refrigerate.

- Medium

- One Person

- Global Technology

- Tropical Climate

- Monsoon Climate

- Food Processing

- Ideas

- Small Business

- Products

- Practical Action Update

- Requested translation to Spanish

- Less than 50 US$

- Small Industry

- Application

- Oil

- Requested translation to French

- Requested translation to Hindi

- Requested translation to Portuguese

- Requested translation to spanish

- Stub