What to Do with Neem Seeds

Contents

- 1 Neem Seeds

- 2 How to Grow Neem Trees

- 3 How to Use Neem as a Natural Pesticide

- 4 How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- 5 Small Scale Oilseed Processing - Technical Brief

- 5.1 The policy environment

- 5.2 Raw material supply

- 5.3 Marketing

- 5.4 Health and safety

- 5.5 Methods of extraction

- 5.6 Equipment required

- 5.7 Shelling or dehulling

- 5.8 Heating or conditioning

- 5.9 Expelling

- 5.10 Filtration

- 5.11 Production capacity

- 5.12 Equipment suppliers

- 5.13 References and further reading

- 5.14 Useful addresses

- 5.15 Related Articles

- 5.16 Categories

Neem Seeds

Introduction

Native to India and Burma, neem is a botanical cousin of mahogany. It is tall and spreading like an oak and bears masses of honey-scented white flowers like a locust. Its complex foliage resembles that of walnut or ash, and its swollen fruits look much like olives. It is seldom leafless, and imparts shade throughout the year.

Reforestation

Under normal circumstances neem's seeds are viable for only a few weeks, but earlier this century people somehow managed to introduce this Indian tree to West Africa, where it has since grown well. Near Mecca, for example, a Saudi philanthropist planted a forest of 50,000 neems to shade and comfort the two million pilgrims. Caribbean, where it is being used to help reforest several nations. Neem is already a major tree species in Haiti for instance.

Insecticide

But neem is far more than a tough tree that grows vigorously in difficult sites. Among its many benefits, the one that is most unusual and immediately practical is the control of farm and household pests. Some entomologists now conclude that neem has such remarkable powers for controlling insects that it will usher in a new era in safe, natural pesticides: neem compounds usually leave the pests alive for some time, but so repelled, debilitated, or hormonally disrupted that crops, people, and animals are protected.

Extracts from its extremely bitter seeds and leaves may, in fact, be the ideal insecticides: they attack many pestiferous species; they seem to leave people, animals, and beneficial insects unharmed; they are biodegradable; and they appear unlikely to quickly lose their potency to a buildup of genetic resistance in the pests.

For centuries, India's farmers have known that the trees withstand the periodic infestations of locusts. Indian scientists took up neem research as far back as the 1920s, but their work was little appreciated elsewhere until 1959 when a German entomologist witnessed a locust plague in the Sudan. During this onslaught of billions of winged marauders, Heinrich Schmutterer noticed that neem trees were the only green things left standing: although the locusts settled on the trees in swarms, they always left without feeding. To find out why, he and his students have studied the components of neem ever since.

Schmutterer's work (as well as a 1962 article by three Indian scientists showing that neem extracts applied to vegetable crops would repel locusts) spawned a growing amount of lively research.

Like most plants, neem deploys internal chemical defences to protect itself against leaf- chewing insects. Its chemical weapons are extraordinary, however. In tests over the last decade, entomologists have found that neem materials can affect more than 200 insect species as well as some mites, nematodes, fungi, bacteria, and even a few viruses. The tests have included several dozen serious farm and household pests - Mexican bean beetles, Colorado potato beetles, locusts, grasshoppers, tobacco budworms, and six species of cockroaches, for example. Success has also been reported on cotton and tobacco pests in India, Israel, and the United States; on cabbage pests in Togo, Dominican Republic, and Mauritius; on rice pests in the Philippines; and on coffee bugs in Kenya. And it is not just the living. plants that are shielded. Neem products have protected stored corn, sorghum, beans, and other foods against pests for up to 10 months in some very sophisticated controlled experiments and field trials.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture have been studying neem since 1972. In laboratory experiments, they have found that the plant's ingredients foil even some of America's most voracious garden pests. For instance, in one trial each half of several soybean leaves was sprayed with neem extracts and placed in a container with Japanese beetles. The treated halves remained untouched, but within 48 hours the other halves were consumed right down to their woody veins. In fact, the Japanese beetles died rather than eat even tiny amounts of neem-treated leaf tissue. In field tests, neem materials have yielded similarly promising results. For instance, in one test in Ohio, soybeans sprayed with neem extract stayed untouched for up to 14 days, untreated plants in the same field were chewed to pieces by various species of insects, seemingly overnight.

Neem contains several active ingredients, and they act in different ways under different circumstances. These compounds bear no resemblance to the chemicals in today's synthetic insecticides. Chemically, they are distant relatives of steroidal compounds, which include cortisone, birth-control pills, and many valuable pharmaceuticals. Composed only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, they have no atoms of chlorine, phosphorus, sulfur, or nitrogen (such as are commonly found in synthetic pesticides). Their mode of action is thus also quite different.

Neem products are unique in that (at least for most insects) they are not outright killers. Instead, they alter an insect's behavior or life processes in ways that can be extremely subtle. Eventually, however, the insect can no longer feed or breed or metamorphose, and can cause no further damage.

For example, one outstanding neem component, azadirachtin, disrupts the metamorphosis of insect larvae. By inhibiting molting, it keeps the larvae from developing into pupae, and they die without producing a new generation. In addition, azadirachtin is frequently so repugnant to insects that scores of different leaf-chewing species - even ones that normally strip everything living from plants - will starve to death rather than touch plants that carry traces of it.

Another neem substance, salannin, is a similarly powerful repellent. It also stops many insects from touching even the plants they normally find most delectable. Indeed, it deters certain biting insects more effectively than the synthetic chemical called "DEET" (N,N-diethy- lm-toluamide), which is now found in hundreds of consumer insect repellents.

To obtain the insecticides from this tree is simple (at least in principle). The leaves or seeds are merely crushed and steeped in water, alcohol, or other solvents. For some purposes, the resulting extracts can be used without further refinement.

These pesticidal "cocktails," containing 4 major and perhaps 20 minor active compounds, can be astonishingly effective. In concentrations of less than one-tenth of a part per million, they affect certain insects dramatically. In trials in The Gambia, for example, these crude neem extracts compared favorably with the synthetic insecticide malathion in their effects on some of the pests of vegetable crops. In Nigeria, they equaled the effectiveness of DDT, Dieldrin, and other insecticides. And elsewhere in the world these plant products have often showed results as good as those of standard pesticides.

Although pests can become tolerant to a single toxic chemical such as malathion, it seems unlikely that they can develop genetic resistance to neem's complex blend of compounds - many functioning quite differently and on different parts of an insect's life cycle and physiology:For example, even after being exposed to neem for 35 successive generations, diamondback moths remained as susceptible as they had been at the beginning.

Another valuable quality is that some neem compounds act as systemic agents in certain plant species. That is, they are absorbed by, and transported throughout, the plants. In such cases, aqueous neem extracts can merely be sprinkled on the soil. The ingredients are then absorbed by the roots, pass up through the stems, and perfuse the upper parts of the plant. In this way, crops become protected from within. In trials, the leaves and stems of wheat, barley, rice, sugarcane, tomatoes, cotton, and chrysanthemums have been protected from certain types of damaging insects for 10 weeks in this way.Because systemic materials are inside the plant, they cannot be washed off by rain.

Toxicity for warm blooded animals and Mammals

Perhaps the most important quality is that neem products appear to have little or no toxicity to warm-blooded animals. This safety to mammals apparently extends to people. The deaths of a few young children in Malaysia in the 1980s have been linked to the doses of neem-seed oil forced on them by their parents. (Like the previous use of castor oil in the Western world, neem oil in Asia is considered a cure-all for some childhood illnesses.) However, other than this, no hazard has been documented under conditions of normal usage. For one thing, neem extracts show no mutagenicity in the Ames test, which detects potential carcinogens. For another, people in India have been adding neem leaves to their grain stores for centuries to keep weevils away. Thus, for many generations millions have been eating traces of neem on a daily basis.

Medicinal qualities

Certain neem products may even benefit human health. The seeds and leaves contain compounds with demonstrated antiseptic, antiviral, and antifungal activity. There are also hints that neem has anti inflammatory, hypotensive, and anti-ulcer effects. There is a potential indirect benefit to health as well. Neem leaves contain an ingredient that disrupts the fungi that produce aflatoxin on moldy peanuts, corn, and other foods - it leaves the fungi alive, but switches off their ability to produce aflatoxin, the most powerful carcinogen known. Neem could prove valuable for Dental hygiene: Research has shown, for example, that compounds in neem bark are strongly antiseptic. Also, tests in Germany have proved that neem extracts prevent tooth decay, as well as both preventing and healing inflammations of the gums. Neem is now used as the active ingredient in certain popular toothpastes in Germany and India.

Contraceptive properties

Researchers have recently found that neem might be able to play a part in controlling population growth. Materials from the seeds have been shown to have contraceptive properties. The oil is a strong spermicide and, when used intravaginally, has proven effective in reducing the birth rate in laboratory animals. A recent test involving the wives of more than 20 Indian Army personnel has further demonstrated its effectiveness. Other neem compounds show early promise as the long-sought oral birth-control pill for men. This is just an intriguing hint at present; however, in exploratory trials they reduced fertility in male monkeys and a variety of other male mammals without inhibiting sperm production. In addition, the effects seemed to be temporary, which would be a big selling point that could help its rapid and widespread adoption.

Global potential of the use of Neem

All of this is potentially of vital importance for the world's poorest countries, many of which have high rates of population growth, severe problems with various agricultural pests, and a widespread lack of even basic medicine. The neem tree will grow in many Third World regions, and it can grow on certain marginal lands where it will not compete with food crops. Thus, it could bring good health and better crop yields within the reach of farmers too poor to buy pharmaceuticals or farm chemicals. It makes feasible the concept of producing one's own pesticide because the active materials can be extracted from the seeds, even at the farm or village level. Extracting the seeds requires no special skills or sophisticated machinery, and the resulting products can be applied using low-technology methods.

Neem also seems particularly appropriate for developing country use because it is a perennial and requires little maintenance. It appeals to people in both rural and urban areas because (unlike most trees) its leaves, fruits, seeds, and various other parts can be used in a multitude of ways. Moreover, it can grow quickly and easily and does not necessarily displace other crops.

In trials in the USA, crude alcohol extracts of neem seeds proved effective at very low concentrations against 60 species of insects, 45 of which are extremely damaging to American crops and stored products - causing billions of dollars of losses to the nation each year. They included sweet-potato whitefly, serpentine leafminers (which attack vegetable and flower crops), gypsy moth (which causes millions of dollars of losses to homeowners and the forest industry), and several species of cockroach.

Neem production and processing also provides employment and generates income in rural communities - perhaps a small, but nonetheless valuable, benefit in these days of mass flight to the cities in a desperate search for jobs. It could be a useful export as well; a ton of neem seed already sells at African ports (Dakar, for example) at more than twice the price of peanuts. On top of all that, neem by-products (the seedcake and leaves, in particular) actually may improve the local soils and help foster sustainable crop production.

Although neem's ability to promote health and its value as a safe pest control is still only in the realm of possibility, there is no doubt that neem trees can provide the poor and the landless with oil, feed, fertilizer, wood, and other essential resources. In its crude state the oil from the seeds can have a strong garlic odor, but even in that form it can be used for heating, lighting, or crude lubricating jobs. Refined, it loses its unpleasant smell and is used in soaps, cosmetics, disinfectants, and other industrial products.

Neem cake, a solid material left after the oil is pressed from the seeds, is also useful. Broadcast over farm fields, it provides organic matter as well as some fertility to the soil. More important, it controls several types of soil pests. It is, for example, notably effective against nematodes, those virulent microscopic worms that suck the life out of many crops. Cardamom farmers in southern India claim that neem cake is as effective as the best nematode-suppressing commercial products.

Because neem is a tree, its large-scale production promises to help alleviate several global environmental problems: deforestation, desertification, soil erosion, and perhaps even (if planted on a truly vast scale) global warming. Its extensive, deep roots seem to be remarkably effective at extracting nutrients from poor soils. These nutrients enter the topsoil as the leaves and twigs fall and decay. Thus, neem can help return to productive use some worn-out lands that are currently unsuited to crops. It is so good for this purpose that a 1968 United Nations report called a neem plantation in northern Nigeria "the greatest boon of the century" to the local inhabitants.

For all its apparent promise, however, the research on neem and the development of its products are not receiving the massive support that might seem justified. Indeed, all the promise mentioned above is currently known to only a handful of entomologists, foresters, and pharmacologists - and, of course, to the traditional farmers of South Asia. Much of the enthusiasm and many of the claims are sure to be tempered as more insights are gained and more field operations are conducted.

Nonetheless, improving pest control, bettering health, assisting reforestation, and perhaps checking overpopulation appear to be just some of the benefits if the world will now pay more attention to this benevolent tree.

Related Articles

References and further reading

After: Neem: A Tree for Solving Global Problems (BOSTID, 1992, 127 p.) http://www.cd3wd.com/CD3WD_40/CD3WD/AGRIC/B08NEE/EN/B1163_17.HTM http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=1924&page=14

Categories

How to Grow Neem Trees

Neem in Short

- WHAT SORT OF SOIL SUITS THE NEEM ?

The Neem grows on almost all types of soils including clayey, saline and alkaline soils, with pH upto 8.5, but does well on black cotton soil and deep, well-drained soil with good sub-soil water. Unlike most other multipurpose tree species, it thrives well on dry, stony, shallow soils and even on soils having hard calcareous or clay pan, at a shallow depth. The tree improves the soil fertility and water-holding capacity as it has a unique property of calcium mining, which changes the acidic soils into neutral.

- HOW MUCH WATER DOES IT NEED ?

Neem tree needs little water and plenty of sunlight. The tree grows naturally in areas where the rainfall is in the range of 450 to 1200 mm. However, it has been introduced successfully even in areas where the rainfall is as low as 200 – 250 mm. It cannot withstand water-logged areas and poorly drained soils. Neem makes land more fertile

- HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE TO REACH MATURITY ?

The Neem grows slowly during the first year of planting. Young neem plants cannot tolerate intensive shade, frost or excessive cold. A Neem tree normally begins to bear fruit between 3 and 5 years and becomes fully productive in 10 years. A mature tree produce 30 – 50 kg. fruit every year

- HOW LONG DOES THE TREE LIVE ?

It is estimated that a Neem tree has a productive life span of 150 – 200 years

- WHERE CAN I GET THE SEED / SAPLING ?

- HOW TO PLANT NEEM TREES ?

The seeds should be as fresh as possible as older seeds often do not germinate. Provided that only a few trees are to be planted, and there is sufficient moisture available, with minimum weeds, the seeds may be sown directly into the ground. Two to three seeds are placed together about 1 cm deep in loose soil. After germination, only the strongest plant should be retained. When planting a large number, it is advisable to cultivate young plants first in pots, trays or plastic bags. After 3 months, they should be transplanted into the ground. When using bags or pots care should be taken that the plants are not allowed to develop to a stage where the tap root has pierced the bottom and has to be shortened before transplantation. This weakens the trees and substantially slows their growth.

Other Names

En: neem, Indian lilac, Fr: azadira d'Inde, margousier, azidarac, azadira Pt: margosa (Goa) Es: margosa, nim De: Niembaum Hindi: neem, nimb Burmese: tamar, tamarkha Urdu: nim, neem Punjabi: neem Tamil: vembu, veppan Sanskrit: nimba, nimbou, arishtha (reliever of sickness) Sindhi: nimmu Sri Lanka: kohomba Farsi: azad darakht i hindi (free tree of India), nib Malay: veppa Singapore: kohumba, nimba Indonesia: mindi Nigeria: dongoyaro Kiswahili: mwarubaini (muarobaini)

Neem is a member of the mahogany family, Meliaceae. It is today known by the botanic name Azadirachta Indica A. Juss. In the past, however, it has been known by several names, and some botanists formerly lumped it together with at least one of its relatives. The result is that the older literature is so confusing that it is sometimes impossible to determine just which species is being discussed.(Previous botanic names were Melia indica and M. azadirachta. The latter name (not to mention neem itself) has sometimes been confused with M. azedarach, a West Asian tree commonly known as Persian lilac, bakain, dharak, or chinaberry. The taxonomy of all these closely related species is so complex that some botanists have recognized as many as 15 species; others, as few as 2.)

Uses of the Neem Tree and seeds

The neem tree is a robust tree vartiety growing in a wide range of climates, from tropical to arid climates and can therefore be used for reforestation purposes. Neem has more than 100 unique bio-active compounds, which have potential applications in agriculture, animal care, public health, and for even regulating human fertility. The seeds are used in different forms for their very powerful insecticide effect on a wide range of pests and their armlessness ( at this stage of knowledge) for warmblooded animals and mammals. It can also be used against mosquito proliferation, as insect reppellent and to protect crops agains locusts infestations. Different preparations are used for various medicinal purposes among which contraceptive effect is being researched about. See the article: What to Do with Neem Seeds

DESCRIPTION

Neem trees are attractive broad-leaved evergreens that can grow up to 30 m tall and 2.5 m in girth. Their spreading branches form rounded crowns as much as 20 m across. They remain in leaf except during extreme drought, when the leaves may fall off. The short, usually straight trunk has a moderately thick, strongly furrowed bark. The roots penetrate the soil deeply, at least where the site permits, and, particularly when injured, they produce suckers.

This suckering tends to be especially prolific in dry localities.

Neem can take considerable abuse. For example, it easily withstands pollarding (repeated lopping at heights above about 1.5 m) and its topped trunk resprouts vigorously. It also freely coppices (repeated lopping at near-ground level). Regrowth from both pollarding and coppicing can be exceptionally fast because it is being served by a root system large enough to feed a full-grown tree.

The small, white, bisexual flowers are borne in axillary clusters. They have a honeylike scent and attract many bees. Neem honey is popular, and reportedly contains no trace of azadirachtin.

The fruit is a smooth, ellipsoidal drupe, up to almost 2 cm long. When ripe, it is yellow or greenish yellow and comprises a sweet pulp enclosing a seed. The seed is composed of a shell and a kernel (sometimes two or three kernels), each about half of the seed's weight. It is the kernel that is used most in pest control. (The leaves also contain pesticidal ingredients, but as a rule they are much less effective than those of the seed.)

A neem tree normally begins bearing fruit after 3-5 years, becomes fully productive in 10 years, and from then on can produce 30- to 100kg of fruits annually, depending on rainfall, insolation, soil type, and ecotype or genotype.It may live for more than two centuries.

Fifty kg of fruit yields 30kg of seed, which gives 6kg of oil and 24kg of seed cake.

Figure

DISTRIBUTION

Neem is thought to have originated in Assam and Burma (where it is common throughout the central dry zone and the Siwalik hills). However, the exact origin is uncertain: some say neem is native to the whole Indian subcontinent; others attribute it to dry forest areas throughout all of South and Southeast Asia, including Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

It is in India that the tree is most widely used. It is grown from the southern tip of Kerala to the Himalayan hills, in tropical to subtropical regions, in semiarid to wet tropical regions, and from sea level to about 700 m elevation.

As already noted, neem was introduced to Africa earlier this century. It is now well established in at least 30 countries, particularly those in the regions along the Sahara's southern fringe, where it has become an important provider of both fuel and lumber. Although widely naturalized, it has nowhere become a pest. Indeed, it seems rather well "domesticated": it appears to thrive in villages and towns.

Over the last century or so, the tree has also been established in Fiji, Mauritius, the Caribbean, and many countries of Central and South America. In some cases it was probably introduced by indentured laborers, who remembered its value from their days of living in India's villages. In other cases it has been introduced by foresters. In the continental United States, small plantings are prospering in southern Florida, and exploratory plots have been established in southern California and Arizona.

PROPAGATION

The tree is easily propagated - both sexually and vegetatively. It can be planted using seeds, seedlings, saplings, root suckers, or tissue culture. However, it is normally grown from seed, either planted directly on the site or transplanted as seedlings from a nursery.

The seeds are fairly easy to prepare. The fruit drops from the trees by itself; the pulp, when wet, can be removed by rubbing against a coarse surface; and (after washing with water) the clean, white seeds are obtained. In certain nations - Togo and Senegal, for example - people leave the cleaning to the fruit bats and birds, who feed on the sweet pulp and then spit out the seeds under the trees.

It is reputed that neem seeds are not viable for long. It is generally considered that after 2-6 months in storage they will no longer germinate. However, some recent observations of seeds that had been stored in France indicated that seeds without endocarp had an acceptable germinative capacity (42 percent) after more than 5 years.(Information from Y. Roederer and R. Bellefontaine. Refrigeration is also said to extend the viability.) According to the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net),the viability of fresh seed decreases rapidly after two weeks, and improperly stored seeds have low germination rates. Ripe seed should be collected from the tree and processed immediately. First the pulp is removed and the seeds are washed clean. Seeds are air dried for 3-7 days in the shade, or until the moisture content is about 30%. They can then be stored for up to four months if kept at 15°C. Seed will remain viable even longer if dried to 6-7% moisture content and refrigerated in sealed containers at 4° C.

They recommend to sow seed in nursery beds in rows 15-25 cm apart, and 2.5-5 cm spacing within the rows. Seedlings can be pricked out when two pairs of leaves have developed (1-2 months), or the rows should be thinned to 15 cm x 15 cm spacing. Plastic pots are commonly used to produce neem seedlings, although rigid container systems are used in Haiti with success. Seeds should be sown horizontally at a depth of 1 cm. Fresh seeds will have the highest germination rate, and seedlings will emerge within in 1-3 weeks. Removal of the seed coat may increase germination rates for stored seeds. Both bare-root and containerized seedlings should be raised under partial shade for the first 1-2 months, or until about 30 cm tall, then gradually exposed to full sunlight.

Bare-rooted seedlings are usually kept in the nursery for 1-2 years before outplanting. The roots and shoots of seedlings lifted from nursery beds should be pruned before transplanting. Bare-rooted seedlings can also be prepared for stump planting. Stumps are made from 1-2 year old seedlings by trimming the root to 20-22 cm root and the shoot to 5 cm. Containerized seedlings should be outplanted after 3-4 months in the nursery, when they reach 30-50 cm. Fuelwood plantations are laid out at a 2.5 m x 2.5 m spacing, and then later thinned to 5 m x 5 m. The recommended spacing for windbreaks is 4 m x 2 m. Neem trees managed to maximize fruit yield should be more widely spaced to allow the crown to develop fully.

GROWTH

The tree is said to grow "almost anywhere" in the lowland tropics. However, it generally performs best in areas with annual rainfalls of 400-1,200 mm. It thrives under the hottest conditions, where maximum shade temperature may soar past 50°C, but it will not withstand freezing or extended cold. It does well at elevations from sea level to perhaps 1,000 m near the equator. The taproot (at least in young specimens) may be as much as twice the height of the tree.

Neem is renowned for good growth on dry, infertile sites. It performs better than most trees where soils are sterile, stony, and shallow, or where there is a hardpan near the surface. The tree also grows well on some acid soils. Indeed, it is said that the fallen neem leaves, which are slightly alkaline (pH 8.2), are good for neutralizing acidity in the soil. On the other hand, neem cannot stand "wet feet," and quickly dies if the site becomes waterlogged.

Neem often grows rapidly. It can be cut for timber after just 5-7 years. Maximum yields reported from northern Nigeria (Samaru) amounted to 169 m3 of fuelwood per hectare after a rotation of 8 years. Yields in Ghana were recorded between 108 and 137 m3 per hectare in the same time.

Weeds seldom affect growth. Except in the case of very young plants, neem can dominate almost all competitors. In fact, the trees themselves may become "weeds." They spread widely under favorable site conditions, since the seeds are distributed by birds, bats, and baboons. For the same reason, natural regeneration under old trees is often abundant. But for all that, in virtually every place it grows neem is considered a boon, not a bane. People almost always like to see more neems coming up.

PROBLEMS

Neem is renowned for its robust growth and resilience to harsh conditions, but, like all living things, it has various shortcomings, some of which are discussed below.

Pests

By and large, most neem trees are reputed to be remarkably pest free; however, in Nigeria

14 insect species and I parasitic plant have been recorded as pests. Few of the attacks were serious, and the trees almost invariably recovered, although their growth and branching may have been affected.

However, in recent years a more serious threat has emerged. In some parts of Africa (mainly in the Lake Chad Basin), a scale insect (Aonidiella orientalis) has become a serious pest. This and other scale insects sometimes infest neem trees in central and south India. They feed on sap, and although they do little harm to mature trees, they may kill young ones. Now that one type has been detected in Africa, the impact could be severe. (It has been suggested that a drastic lowering of the groundwater level around Lake Chad - which nearly dried out during a drought in the Sahel - was the main reason for the outbreak. This is perhaps true; scale insects are usually "secondary" pests that multiply best on plants that are already damaged by other pests or other adverse environmental factors.)

Other insect pests include the following:

· The scale insect Pinnaspis strachani (very common in Asia, Africa, and Latin America);

· Leaf-cutting ants Acromyrmex spp. (common defoliators of young neem trees in Central and South America);

· The tortricid moth Adoxophyes aurata (attacks leaves in Asia including Papua New Guinea);

· The bug Helopeltis theivora (considered a serious neem pest in southern India); and

· The pyralid moth Hypsipyla sp. (attacks neem shoots in Australia).

Even though neem timber is renowned for termite resistance, termites sometimes damage, or even kill, the living trees. They usually attack only sickly specimens, however.

Diseases

Despite the fact that the leaves contain fungicidal and antibacterial ingredients, certain microbes may attack different parts of the tree, including the following:

· Roots (root rot, Ganoderma lucidum, for instance);

· Stems and twigs (the blight Corticium salmonicolor, for example);

· Leaves (a leaf spot, Cercospora subsessilis; powdery mildew, Oidium sp., and the bacterial blight Pseudomonas azadirachtae);(5) and

· Seedlings (several blights, rots, and wilts - including Sclerotium, Rhizoctonia, and Fusarium).(6)

A canker disease that discolors the wood and seems to coincide with a sudden absorption of water after long droughts has also been observed.

Nutrient Deficiencies

A lack of zinc or potassium drastically reduces growth. Trees affected by zinc deficiency show chlorosis of the leaf tips and leaf margins, their shoots exude much resin, and their older leaves fall off. Those with potassium deficiency show leaf tip and marginal chlorosis and die back (necrosis).

Other Problems

Fire kills neem seedlings outright. However, mature trees almost always regrow, especially if the dead parts are quickly cut away.

High winds are a potential problem. Large trees frequently snap off during hurricanes, cyclones, or typhoons. Neem is therefore a poor candidate for planting in areas prone to such violent storms.

Seedlings regenerating beneath stands of neem are sensitive to sudden exposure to intense sunlight. Thus, clear-felling neem trees normally produces a massive seedling kill, especially if the seedlings are small.

In some localities rats and porcupines kill young trees by gnawing the bark around the base. Even when not causing any physical damage, rodents can be pests: wherever they are numerous, the fruits may disappear before the farmer can harvest them.

Neem, with its intensely bitter foliage, is not a preferred browse, but if nothing else is available goats and camels will eat it. In fact, in Asia goats and camels have been known to browse young neem trees so severely in times of scarcity that the plants died. In Africa neem is generally ignored by livestock (which makes the tree easy to establish even within villages and courtyards). The reason that livestock treat neem differently in Asia and Africa is unknown at present. It may be differences in the tree specimens, or in the animals' preferences or past experiences.

Related Articles

- How to Grow Neem Trees

- What to Do with Neem Seeds

- How to Use Neem as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Control Termite without Chemicals

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Use Garlic as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Use Chillies as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Grow Shea Trees (Karité, Nku, Bambuk Butter tree)

- How to Purify Water with Moringa Seeds

- How to Grow Moringa Trees

References and further reading

- Neem: A Tree for Solving Global Problems (BOSTID, 1992, 127 p.) http://www.cd3wd.com/CD3WD_40/CD3WD/AGRIC/B08NEE/EN/B1163_17.HTM

Books available at the Neem Foundation http://www.neemfoundation.org:

- Guidelines for Plantation (Marathi) Dr. H.M. Behl

- Kadu Nimb Anni Ayurveda (Marathi) Usha Rajendra Joshi

- Neem in Ayurveda (Hindi) Vaidya Suresh Chaturvedi

- Neem Kranti (Hindi) Radhekurnana Dubey

- Neem Yug (Hindi) R.A.S. Khangar

- The Neem Tree Prof. H. Schmutterer

- Proceedings Neem ‘99 Conf. Dr. H.M. Behl

- Neem: A User’s Guide K. Vijayalakshmi, K. Radha & S. Vandana

- Formulation of Neem – Based Products / Pesticides Dr. R.T. Gahukar

- Collection, Processing, Storage of Neem Seeds & Guidelines for Plantation Neem Foundation

- Neem in Ayurveda (English) Vaidya Suresh Chaturvedi

- Neem in Plant Protection Dr. R.T. Gahukar

- Proceedings of NEEM 2002, World Neem Conference, Mumbai – (Vol. 1 & 2) Neem Foundation

- Botanical Pesticides in Integrated Pest Management Dr. M.S. Chari /G. Ramprasad

- Neem: Application in Agriculture, Health Care & Environment Neem Foundation

- Development and Ecological Role of Neem in India Kamal Nayan Kabra

- Neem N.S. Parmar /N.S. Randhawa

- Monograph on Neem Dr. D. N. Tewari

- Neem: Azadirachta indica A. Juss Dr. R. P. Singh /Dr. R.C. Saxena

- Neem and Environment (Vol. 1 & 2) Dr. Singh

- Project Report on Plantation

- Neem: The Hidden Wealth – CD Films Division

Contact

Neem Foundation

67- A, Vithalnagar Society / Road # 12, JVPD Scheme / Mumbai – 400 049 / India

Tel: 0091 22 26206367 / 26207867 / 26231709

Fax: 0091-22-26207508

E-mail:info@neemfoundation.org

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Categories

How to Use Neem as a Natural Pesticide

Other Names

En: neem, Indian lilac, Fr: azadira d'Inde, margousier, azidarac, azadira Pt: margosa (Goa) Es: margosa, nim De: Niembaum Hindi: neem, nimb Burmese: tamar, tamarkha Urdu: nim, neem Punjabi: neem Tamil: vembu, veppan Sanskrit: nimba, nimbou, arishtha (reliever of sickness) Sindhi: nimmu Sri Lanka: kohomba Farsi: azad darakht i hindi (free tree of India), nib Malay: veppa Singapore: kohumba, nimba Indonesia: mindi Nigeria: dongoyaro Kiswahili: mwarubaini (muarobaini)

Description

Among Neem's many benefits, the one that is most immediately practical is the control of farm and household pests.

Some entomologists now conclude that neem has such remarkable powers for controlling insects that it will usher in a new era in safe, natural pesticides: neem compounds usually leave the pests alive for some time, but so repelled, debilitated, or hormonally disrupted that crops, people, and animals are protected.

Extracts from its extremely bitter seeds and leaves may, in fact, be the ideal insecticides: they attack many pestiferous species; they seem to leave people, animals, and beneficial insects unharmed; they are biodegradable; and they appear unlikely to quickly lose their potency to a buildup of genetic resistance in the pests.

For centuries, India's farmers have known that the Neem trees withstand the periodic infestations of locusts. Neem extracts applied to vegetable crops repel locusts (Heinrich Schmutterer, 1962).

Like most plants, neem deploys internal chemical defences to protect itself against leaf- chewing insects. Its chemical weapons are extraordinary, however.

Neem contains several active ingredients, and they act in different ways under different circumstances.

These compounds bear no resemblance to the chemicals in today's synthetic insecticides. Chemically, they are distant relatives of steroidal compounds, which include cortisone, birth-control pills, and many valuable pharmaceuticals. Composed only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, they have no atoms of chlorine, phosphorus, sulfur, or nitrogen (such as are commonly found in synthetic pesticides). Their mode of action is thus also quite different.

Neem products are unique in that (at least for most insects) they are not outright killers. Instead, they alter an insect's behavior or life processes in ways that can be extremely subtle. Eventually, however, the insect can no longer feed or breed or metamorphose, and can cause no further damage.

For example, one outstanding neem component, azadirachtin, disrupts the metamorphosis of insect larvae.

By inhibiting molting, it keeps the larvae from developing into pupae, and they die without producing a new generation. In addition, azadirachtin is frequently so repugnant to insects that scores of different leaf-chewing species - even ones that normally strip everything living from plants - will starve to death rather than touch plants that carry traces of it.

Another neem substance, salannin, is a similarly powerful repellent.

It also stops many insects from touching even the plants they normally find most delectable. Indeed, it deters certain biting insects more effectively than the synthetic chemical called "DEET" (N,N-diethy- lm-toluamide), which is now found in hundreds of consumer insect repellents.

These pesticidal "cocktails," containing 4 major and perhaps 20 minor active compounds, can be astonishingly effective. In concentrations of less than one-tenth of a part per million, they affect certain insects dramatically. In trials in The Gambia, for example, these crude neem extracts compared favorably with the synthetic insecticide malathion in their effects on some of the pests of vegetable crops. In Nigeria, they equaled the effectiveness of DDT, Dieldrin, and other insecticides. And elsewhere in the world these plant products have often showed results as good as those of standard pesticides.

Although pests can become tolerant to a single toxic chemical such as malathion, it seems unlikely that they can develop genetic resistance to neem's complex blend of compounds - many functioning quite differently and on different parts of an insect's life cycle and physiology:For example, even after being exposed to neem for 35 successive generations, diamondback moths remained as susceptible as they had been at the beginning.

Another valuable quality is that some neem compounds act as systemic agents in certain plant species.

That is, they are absorbed by, and transported throughout, the plants. In such cases, aqueous neem extracts can merely be sprinkled on the soil. The ingredients are then absorbed by the roots, pass up through the stems, and perfuse the upper parts of the plant. In this way, crops become protected from within. In trials, the leaves and stems of wheat, barley, rice, sugarcane, tomatoes, cotton, and chrysanthemums have been protected from certain types of damaging insects for 10 weeks in this way.Because systemic materials are inside the plant, they cannot be washed off by rain.

Pest toxicity

In tests over the last decade, entomologists have found that neem materials can affect more than 200 insect species as well as some mites, nematodes, fungi, bacteria, and even a few viruses. The tests have included several dozen serious farm and household pests

- Mexican bean beetles,

- Colorado potato beetles,

- locusts, grasshoppers,

- tobacco budworms,

- and six species of cockroaches, for example.

Success has also been reported on:

- cotton and tobacco pests in India, Israel, and the United States;

- cabbage pests in Togo, Dominican Republic, and Mauritius;

- rice pests in the Philippines;

- coffee bugs in Kenya.

- Neem products have protected stored corn, sorghum, beans, and other foods against pests for up to 10 months in some very sophisticated controlled experiments and field trials.

- Neem extracts will protect Soybeans from the Japanese beetles: In one test in Ohio, soybeans sprayed with neem extract stayed untouched for up to 14 days, untreated plants in the same field were chewed to pieces by various species of insects, seemingly overnight

Receipes

To obtain the insecticide from Neem is simple (at least in principle). The leaves or seeds are merely crushed and steeped in water, alcohol, or other solvents. For some purposes, the resulting extracts can be used without further refinement.

For example, grind 1kg of nuts from the neem fruit, mix the powder with 15 litres of water and leave to soak for 24 hours.

Links

Link to Fourthway's poster "How to make a natural pesticide": http://www.fourthway.co.uk/posters/pages/pesticide.html

Related articles

- How to Grow Neem Trees

- What to Do with Neem Seeds

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Use Neem as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Control Termite without Chemicals

- How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

- How to Use Garlic as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Use Chillies as a Natural Pesticide

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Categories

How to Process Oilseed on a Small Scale

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Small Scale Oilseed Processing - Technical Brief

Most countries in the world have large refineries producing cooking oil from a variety of raw materials including maize, sunflower, soya, coconut, mustard seed and groundnuts. These large centralised plants have the advantage of high efficiency and reduced costs due to the economy of scale. Despite this, in many situations smaller scale decentralised oil extraction can prove to be economic and provide opportunities for income generation. Most commonly, opportunities exist where:

- oil produced in the large refineries does not find its way out to more remote and distant rural areas.

- high transport costs are involved in wide distribution of cooking oil so increasing the price of oil.

- small farmers produce oilseeds such as groundnuts for sale to the large refineries which they then buy back, at high cost, in the form of cooking oil but without the valuable high protein oil cake.

- the crude oil is used to produce added value products, most commonly soap.

- more unusual, high value oilseeds are available; examples include Brazil Nuts, Macadamia Nuts.

Figure 1: Sunflowers grown in Kenya ©Practical Action/Morris Keyonzo

The main risks that need to be considered are:

The policy environment

In many countries the oil processing sector is highly politicised and regulations exist which make entering the market difficult and tend to support the monopoly of the large processors. Large refineries may, for example, insist that farmers sell all their seed under a contract. In other cases seed has to be sold to a central Government marketing board, the board also supplying seed for planting. To determine whether small scale processing is likely to be economic it is most important to first investigate the local situation and regulations.

Raw material supply

Clearly there must be sufficient raw material available locally. One factor that will greatly influence the viability of the enterprise will be the amount of credit needed to purchase a stock of seed. The enterprise should aim to keep the minimum stock of seed but always have enough to continue operating throughout the year. This requires considerable working capital.

Marketing

In general more profit will be made if the cooking oil is packed into retail size bottles. In many countries glass or plastic bottles are difficult to obtain and need to be purchased in large quantities so tying up capital. The possibility of using second-hand bottles should be examined as well as selling in drums to local stores. A survey need to be carried out to make sure that the packaging used meets the demands of customers. (eg size of pack, type of container)

The viability of any oil extraction enterprise depends to a considerable extent on the sale of the oil cake for use in animal feeds and other sub-products. Markets for oil cake must be investigated and demand established before processing starts.

Health and safety

As oil processing is classified as a food processing enterprise it will be subject to local legislation. Care should be taken that standards are understood and met. The particular problem of aflatoxins will require attention. Aflatoxins are natural poisons produced by certain moulds that grow on seeds and nuts. They are of considerable concern to oil seed processors and groundnuts are particularly susceptible to contamination. The growth of aflatoxin producing moulds can be prevented by correct drying and by preventing moisture pickup by raw materials in store. It is most important that those considering establishing an edible oil enterprise should be able to recognise aflatoxin producing moulds and understand how to correctly select and store raw materials. If aflatoxin is present very little passes to the extracted oil, the majority will be found in the cake remaining after extraction. Aflatoxin contaminated cake presents a real danger if incorporated in livestock feeds. As aflatoxin is difficult to remove good practice is essential to prevent any mould growth and so prevent problems.

Not all oilseed crops are suitable for processing at small scale, the most common types that are suitable include groundnut, sunflower, coconut, sesame, mustard seed, oil palm and shea nuts. Typical oil contents of common raw materials are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Common oils and their uses

|

|

. |

. |

|

Castor |

35-55 |

Paints, lubricants |

|

Cotton |

15-25 |

Cooking oil, soaps |

|

Linseed |

35-44 |

Paints |

|

Rape/mustard |

40-45 |

Cooking oil |

|

Sesame |

35-50 |

Cooking oil |

|

Sunflower |

25-40 |

Cooking oil |

|

|

. |

. |

|

Coconut |

35 (Fresh) |

Cooking oil, soaps |

|

Groundnuts |

38-50 |

Cooking oil, soaps |

|

Palm Kernel |

46-57 |

Cooking oil, cosmetics |

|

Shea nuts |

34-44 |

Cooking oil, soaps |

|

Mesocarp Palm fruit |

av. 56 |

Cooking oil, soap |

In many cases the crude extracted oil is not suitable for human consumption until it has been refined to remove undesirable free fatty acids that taste rancid, dark colours and waxes. Refining involves considerable extra equipment costs. The most suitable oils for small and medium scale extraction are those that need little or no refining eg. mustard, sesame, groundnut, sunflower, palm and palm kernel .

Methods of extraction

Five common methods are used to extract oil:

a) Water assisted. Here the finely ground oilseed is either boiled in water and the oil that floats to the surface is skimmed off or ground kernels are mixed with water and squeezed and mixed by hand to release the oil.

b) Manual pressing. Here oilseeds, usually pre-ground, are pressed in manual screw presses. A typical press is shown in diagram 1.

c) Expelling. An expeller consists of a motor driven screw turning in a perforated cage. The screw pushes the material against a small outlet, the "choke". Great pressure is exerted on the oilseed fed through the machine to extract the oil. Expelling is a continuous method unlike the previous two batch systems.

d) Ghanis. A ghani consists of a large pestle and mortar rotated either by animal power or by a motor. Seed is fed slowly into the mortar and the pressure exerted by the pestle breaks the cells and releases the oil. Ghani technology is mainly restricted to the Indian sub-continent.

e) Solvent extraction. Oils from seeds or the cake remaining from expelling is extracted with solvents and the oil is recovered after distilling off the solvent under vacuum.

Most small enterprises will find that small expellers are the best technology choice. Methods such as water extraction and manual pressing only produce small amounts of oil per day, the extraction efficiencies are low and labour requirements high. Solvent extraction while highly efficient involves very substantial capital cost and is only economic at large scale. There are also health and safety risk from using inflammable solvents.

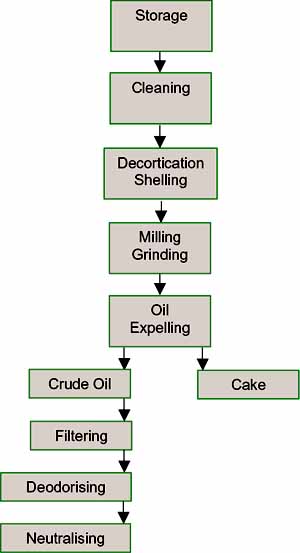

The basic steps involved in processing oilseeds by expeller are shown in the flow diagram below.

Equipment required

The equipment needed to set up a small or medium scale oil extraction enterprise falls into three main categories:

- pre-extraction equipment; eg dehullers, seed/kernel crackers, roasters, mills.

- extraction equipment; manual presses, ghanis, expellers

- equipment for basic refining of the oil; filters, settling tanks.

The specific equipment required will depend on the particular crop being processed, the final oil quality required and the scale of operation. In a small guide it is impossible to cover both the whole range of technical options and possible crops the following section concentrates on one example; the extraction of sunflower and groundnut oil by expeller.

Shelling or dehulling

Most oil bearing seed need to be separated from outer husk or shell. This is referred to as shelling, hulling or decortication. Shelling increases the oil extraction efficiency and reduces wear in the expeller as the husks are abrasive. In general some 10% of husk is added back prior to expelling as the fibre allows the machine to grip or bite on the material.

A wide range of manual and mechanical decorticators are available and typical examples are shown in Figure 2.

After decortication the shell may have to be separated from the kernels by winnowing. At small scale this can be done by throwing the material into the air and allowing the air to blow away the husk. At larger scale mechanical winnowers and seed cleaners are available

Heating or conditioning

Pre-heating the seeds prior to expelling speeds up the release of the oil. Pre-heating is generally carried out in a steam heated kettle mounted above the expeller.

Expelling

A wide range of makes and sizes of expellers are available. In India in particular a number of efficient small or "baby" expellers are available. A typical example with a capacity of up to 100 kg/hr is shown in figure.3. This machine has a central cylinder or cage fitted with eight separate sections or "worms". This flexible system allows single or double-reverse use and spreads wear more evenly along the screw. When the screw becomes worn only individual sections require repair thus reducing maintenance costs. As the material passes through the expeller the oil is squeezed out, exits through the perforated cage and is collected in a trough under the machine. The solid residue, oil cake, exits from the end of the expeller shaft where it is bagged.

Figure 4: Tinytech oil expeller in operation in Zimbabwe ©Practical Action/Keith Machell

Filtration

The crude expelled oil contains solid particles. These can be removed by allowing the oil to stand and then filtering the clear oil by gravity through fine cloth. A better but more expensive method is pumping the crude oil through a filter press.

The typical system described above can be obtained for about $US 4500 (1992 price) and consists of:

Decorticator with blower to remove shell, 150 kg/hr

Boiler, 50 kg steam/hr at 30 psi

Cooker

Expeller 75 -100 kg/hr

Filter pump and press.

If filling into retail packs is planned a simple manual piston filler would be required.

Production capacity

A small mill as described above has the following capacity (based on single shift, 8 hrs/day, 24 days/month)

|

. |

|

|

|

Groundnut Seed |

864 |

248,832 |

|

oil litres |

260 |

74,976 |

|

oilcake |

566 |

163,164 |

|

Sunflower Seed |

720 |

207,360 |

|

oil litres |

159 |

45,888 |

|

oilcake |

522 |

150,444 |

Economic viability will be greatly increased if the mill works double shift.

In terms of employment a small oil mill would provide work for the owner/manager and four workers.

Equipment suppliers

Note: This list of suppliers does not imply endorsement by Practical Action.

Chetan Agro industries

108, Atul Complex, Gondal Road, Opp: Bombay Hotel, RAJKOT - 360 002 INDIA . PHONE : +91-281-2461781 FAX +91-281-2461782 Web: [www.chetantent.com]

Agro Industrial Agency

Near Malaviya Vadi, Gondal Road, Rajkot - 360 002, India

Tel: +91 281 461134/462079/451214, Fax: +91 281 461770

- "Jagdish" Tiny Oil Press: Used for the extraction of vegetable oil from oilseeds. The reverse worm system in the pressing chamber results in the highest recovery of oil. Food Groups: Oilseeds. Capacity: 50 kg/hour, Power: Diesel/Electric

TinyTech Plants Tagore Road, Rajkot - 360 002, India

Tel: +91 281 2480166, 2468485, 2431086, Fax: +91 281 2467552

Website: http://www.tinytechindia.com/

- Oil expellers : Capacity: 125 kg/hour. Power: Electric

- Filter Press: This is suitable for the filtration of oil. It gives transparent, very clean oil without any solid particles. Food Groups: Oilseeds, Capacity: 100-200 litres/hour

Alvan Blanch Chelworth Malmesbury, Wiltshire, SN16 9SG, UK. Tel: +44 (0) 666 577333, Fax: +44 (0) 666 577339

- Expellers / Oil Screw Press - model mini 50: Barrel constructed from separate cast rings spaced apart by shims. The barrels are 60mm diameter by 155mm drainage length with a single piece worm shaft driven from the discharge end through a totally enclosed intermediate chain. The unit is complete with feed hopper, manual feed chute, oil discharge spout and base plate. A versatile, low cost machine, designed to suit village communities or small industries. Suitable for oil and cattle cake. Food Groups: Oilseeds, Capacity: 50 kg/hour input. Power: Diesel/Electric

C S Bell Co 170 West Davis Street, PO Box 291, Tiffin, Ohio, USA, Tel: +1 419 448 0791, Fax: +1 419 448 1203

- No.60 Power Grist Mill: This mill is suitable for use on large and small farms. Adjustable for grinding texture. Includes hopper, feed regulator slide, coarse and fine grinding burrs and 12 inch diameter pulley. Food Groups: Cereals/Oilseeds/Herbs/spices, Capacity: 150 kg/hour, Power: Electric/Manual

Forsberg Agritech India PVT Ltd 123, GIDC Estate, Makarpura, Baroda - 390 010 India. Tel: +91 (0) 265 645752, Fax: +91 (0) 265 641683.

• Pneumatic Aspirator / Winnower

This machine is used for "air washing" of the material to remove all dust, lights and impurities which are lighter than the seed. Winnowing of harvested and threshed seeds.

Food Groups: Cereals/Herbs/spices/Oilseeds

Ashoka Industries Kirama Walgammulla, Sri Lanka, Tel: +94 71 764725

- Oil Expeller: Food Groups: Oilseeds, Capacity: 5 litres/hour. Power: Electric.

Goldin India Equipment PVT Limited

F-29, B.I.D.C. Industrial, Estate, Gorwa, Vadodara - 390 016- Gujarat, India

Tel: +91 (0) 265 3801 168/380 461, Fax: +91 (0) 265 3801 168/380 461

- Screen Air Separator / Grain Cleaners:

Most suited as precleaner before storage of seeds. Variable speed drive ensures accurate quality separations at high capacity. Totally enclosed aspiration system with cyclone provides dust free working in the plant. Food Groups: Cereals/Herbs/spices/Oilseeds/Vegetables Capacity: 100 - 2000 kg/hour. Power: Battery/Electric

Flower Food Company

91/38 Ram Indra Road, Soi 10, Km 4, Bangkok, Thailand. Tel: +66 2 5212203 / 5523420

- Seed Decorticator Machine: Food Groups: Oilseeds, Capacity: 500 kg/hour. Power: Electric

Nigerian Oil Mills Ltd

P.O.Box 264, Atta, Owerri, Imo-State, Nigeria

- Milling Machine / Mills and Grinders

This machine is used for crushing palm kernels, groundnut seeds and moringa seeds to extract oil. Food Groups: Oilseeds/Nuts/Herbs/spices. Power: Electric/Manual - Oil Expeller: This machine is used for crushing palm kernels, groundnut seeds and moringa seeds to extract oil. Food Groups: Oilseeds/Nuts/Herbs/spices. Power: Electric/Manual

Intermech Engineering Ltd P.O. Box 1278, Morogoro, Tanzania

- Oil Expeller: The machine expells oil from sunflower, sesame, neem, moringa, groundnuts, coconut, view details at http://www.intermech.biz

References and further reading

- The Manual Screw Press: For small-scale oil extraction Kathryn H. Potts and Keith Machell, ITDG Publications 1995

- Small Scale Vegetable Oil Extraction S.W. Head et al, NRI, ISBN 085954 387 0

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Small scale oil extraction.

To look at the original document follow this link: http://www.practicalaction.org/?id=technical_briefs_food_processing

Useful addresses

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail:practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk

web:www.practicalaction.org

Related Articles

- How to Make Lime Oil and Juice

- How to Build the ARTI Compact Biogas Digestor

- What to Do with Oil

- How to Recycle Oil

- How to Purify Water with Moringa Seeds

- How to Make Soap

Support the work of howtopedia, help us to continue to write and translate more practical articles on simple technologies!

<paypal />

Categories

- Stub

- Agriculture

- Pest control

- Composting

- Soil

- Forest

- Food Processing

- Health

- Hygiene

- Ideas

- Small Business

- Products

- Principles

- Easy

- Medium

- One Person

- Global Technology

- Rural Environment

- Urban Environment

- Montaneous Environment

- Forest Environment

- Mediterranean Climate

- Tropical Climate

- Arid Climate

- Monsoon Climate

- Prevention

- Howtopedia requested images

- Howtopedia requested drawings

- Requested translation to Spanish

- Requested translation to French

- Pages with broken file links

- Being translated to Spanish

- Requested translation to Hindi

- Requested translation to Bangla

- Requested translation to Indonesian

- Requested translation to Javanese

- Requested translation to Madarin

- Requested translation to Russian

- Requested translation to Swahili

- Requested translation to Tamil

- Crops

- Fruits

- Insects

- Pollution

- Resource Management

- Tree

- Vegetables

- Biodiversity

- Between 50 and 200 US$

- Up to 5 Persons

- Oil

- Seeds

- Practical Action Update

- Requested translation to Arabic