What to Do with Ashes

THIS IS THE FULL TEXT COLLECTION OF ALL RELATED ARTICLES:

Contents

- 1 How to Make soap

- 1.1 Short Description

- 1.2 Description

- 1.2.1 Introduction

- 1.2.2 Ingredients

- 1.2.3 How to make lye from ashes

- 1.2.4 How to make potash

- 1.2.5 How to make soda lye and caustic soda

- 1.2.6 How to prepare tallow

- 1.2.7 How to prepare oil

- 1.2.8 Soapmaking

- 1.2.9 Soft soap

- 1.2.10 Hard soap

- 1.2.11 Problems in soapmaking

- 1.2.12 To improve hard soap

- 1.2.13 Hard soap recipes

- 1.2.14 Medicated soaps

- 1.2.15 More recipes for soft-soap cold process

- 1.2.16 Glossary

- 1.2.17 Equipment list

- 1.3 Difficulties

- 1.4 Success Story

- 1.5 Plans, Illustrations, Posters

- 1.6 Contacts

- 1.7 Links

- 1.8 References and further reading

- 1.9 Related articles

- 1.10 Categories

- 2 How to Build a Winiarski Rocket Stove

How to Make soap

Short Description

- Problem:

- Idea:

- Difficulty:

- Price Range:

- Material Needeed: Ashes, oil or fat, rain water / soft water.

A large iron soap kettle with high sides, a long-handled wooden ladle, a kitchen grater or a meat grinder to make soap flakes, flat wooden boxes, moulds or tubes, cut plastic bottles or plastic tubs, to mould the soap, pieces of cloth, a plate.

- Geographic Area: Global

- Competencies:

- How Many people? From one on

- How Long does it take?

Description

Introduction

With practice, soapmaking is not difficult and is suitable as a small-scale business. It uses simple equipment and vegetable oils or animal fats as raw materials, each of which is likely to be locally available in most countries. However, it is more difficult to produce high-quality hard soap, which in some countries is necessary to compete with imported products or those produced by large-scale manufacturers. There are also certain hazards in producing soap, which any potential producer must be aware of to avoid injury. This technical brief describes the procedures needed to make a variety of simple soaps and includes a number of recipes for different types of soap.

File:P01.jpg

Figure 1: Bina Baroi with some of her finished soap products after soapmaking training from Practical Action Bangladesh. ©Zul/Practical Action

Ingredients

There are three main ingredients in plain soap - oil or fat (oil is simply liquid fat), lye (or alkali) and water. Other ingredients may be added to give the soap a pleasant odour or colour, or to improve its skin-softening qualities. Almost any fat or non-toxic oil is suitable for soap manufacture. Common types include animal fat, avocado oil and sunflower oil. Lyes can either be bought as potassium hydroxide (caustic potash) or from sodium hydroxide (caustic soda), or if they are not available, made from ashes. Some soaps are better made using soft water, and for these it is necessary to either use rainwater or add borax to tap water. Each of the above chemicals is usually available from pharmacies in larger towns.

|

Caution! Lyes are extremely caustic. They cause burns if splashed on the skin and can cause blindness if splashed in the eye. If drunk, they can be fatal. Care is needed when handling lyes and 'green' (uncured) soap. Details of the precautions that should be taken are given below. Because of these dangers, keep small children away from the processing room while soap is being made. |

How to make lye from ashes

Commercial lyes can be bought in tins from pharmacies in larger towns, and these are a standard strength to give consistent results. However, if they are not available or affordable, lye can also be made from ashes. Fit a tap near to the bottom of a large (e.g. 250 litre) plastic or wooden barrel/tub. Do not use aluminium because the lye will corrode it and the soap will be contaminated. Make a filter inside, around the tap hole, using several bricks or stones covered with straw. Fill the tub with ashes and pour boiling water over them until water begins to run from the tap. Then shut the tap and let the ashes soak. The ashes will settle to less than one quarter of their original volume, and as they settle, add more ashes until the tub is full again. Ashes from any burned plant material are suitable, but those from banana leaf/stem make the strongest lye, and those from apple wood make the whitest soap.

If a big barrel is not available, or smaller amounts of soap are to be made, a porcelain bowl or plastic bucket can be used. Fill the bucket with ashes and add boiling water, stirring to wet the ashes. Add more ashes to fill the bucket to the top, add more water and stir again. Let them stand for 12 - 24 hours, or until the liquid is clear, then carefully pour off the clear lye.

The longer the water stands before being drawn off, the stronger the lye will be. Usually a few hours will be enough. Lye that is able to cause a fresh egg to float can be used as a standard strength for soap-making. The strength of the lye does not need to always be the same, because it combines with the fat in a fixed proportion. If a weak lye is used, more lye can be added during the process until all the fat is saponified1.

1 saponification is the name given to the chemical reaction in which lye and fat are converted into one substance -soap

How to make potash

Potash is made by boiling down the lye water in a heavy iron kettle. After the water is driven off, a dark, dry residue known as 'black salts' remains. This is then heated until it melts and the black impurities are burned away to leave a greyish-white substance. This is potash. It can be stored for future soapmaking in a moisture-proof pot to prevent it absorbing water from the air.

How to make soda lye and caustic soda

Mix 1 part quicklime with 3 parts water to make a liquid that has the consistency of cream. Dissolve 3 parts sal soda in 5 parts boiling water, and add the lime cream, stirring vigorously. Keep the mixture boiling until the ingredients are thoroughly mixed. Then allow it to cool and settle, and pour off the lye. Discard the dregs in the bottom. Caustic soda is produced by boiling down the lye until the water is evaporated and a dry, white residue is left in the kettle. Most commercial lyes are caustic soda, and these can be bought and substituted for homemade lye to save time. They are supplied in tins and the lids should be kept tightly fitted to stop the lye absorbing water from the air and forming a solid lump.

|

Care when using lyes, potash or caustic soda You should always take precautions when handling these materials as they are dangerous. Be especially careful when adding them to cold water, when stirring lye water, and when pouring the liquid soap into moulds. Lyes produce harmful fumes, so stand back and avert your head while the lye is dissolving. Do not breath lye fumes. It is worth investing in a pair of rubber gloves and plastic safety goggles. You should also wear an apron or overalls to protect your clothes. If lye splashes onto the skin or into your eyes, wash it off immediately with plenty of cold water. When lye is added to water the chemical reaction quickly heats the water. Never add lye to hot water because it can boil over and scald your skin. Never add water to lye because it could react violently and splash over you. |

How to prepare tallow

Cut up beef suet, mutton fat or pork scraps and heat them over a low heat. Strain the melted fat through a coarse cloth, and squeeze as much fat as possible out of the scraps.

Clean the melted fat by boiling it in water. Use twice as much water as fat, add a tablespoon of salt per 5 kg fat, and boil for ten minutes, stirring thoroughly all the time. Allow it to cool and form a hard cake on top of the water. Lift off the cake of fat and scrape the underside clean. This is then ready to store or use in a soap recipe.

How to prepare oil

Vegetable oils can be extracted from oilseeds, nuts or some types of fruit (see Table 1 and the separate Technical Brief 'Oil Extraction'). They can be used alone or mixed with fat or other types of oil. Note: solid fats and 'saturated' oils (coconut, palm, palm kernel) are more suitable for soapmaking. 'Unsaturated' oils (e.g. safflower, sunflower) may produce soap that is too soft if used alone (see Table 2) and are not recommended.

Soapmaking

There are two types of soap: soft soap and hard soap. Soft soap can be made using either a cold process or a hot process, but hard soap can only be made using a hot process. To make any soap it is necessary to dilute the lye, mix it with the fat or oil, and stir the mixture until saponification takes place (in the processes described below, the word 'fat' is used to mean either fat or oil). The cold process may require several days or even months, depending upon the strength and purity of the ingredients, whereas the hot process takes place within a few minutes to a few hours.

Dispose of soap-making wastes carefully outdoors, do not put them in the drain.

|

Fats |

Oils |

|

Goat fat |

Canola |

|

Lanolin |

Coconut |

|

Lard |

Cottonseed |

|

Mutton fat |

Palm |

|

Pork fat |

Palm kernel |

|

Suet |

Soybean |

|

Tallow( beef fat) |

Table 1: Types of fats and oils used in soapmaking

Soft soap

Cold process

A simple recipe for soft soap uses 12 kg of fat, 9 kg of potash and 26 litres of water. Dissolve the potash in the water and add it to the fat in a wooden tub or barrel. For the next 3 days, stir it vigorously for about 3 minutes several times a day, using a long wooden stick or paddle. Keep the paddle in the mixture to prevent anyone accidentally touching it and being burnt. In a month or so the soap is free from lumps and has a uniform jelly-like consistency. When stirred it has a silky lustre and trails off the paddle in slender threads. Then the soap is ready to use and should be kept in a covered container.

Boiling process

|

Boiling can be very dangerous. Before the process is complete, the soap can get up to 330 degrees F. From 220 degrees F. to 275 degrees F. it has a tendency to splutter or spatter soap out of the pot if it boils too vigorously. There is a chance of fire. Use a pot with high sides. Have a lid close to hand to smother any flames, and if you can a fire extinguisher. Never leave cooking soap unattended. Be sure to wear adequate protection. This includes long gloves and protection for all exposed skin and face ( face shield ). |

Soft soap is also made by boiling diluted lye with fat until saponification takes place. Using the same amounts as above, put the fat into a soap kettle, add sufficient lye to melt the fat and heat it without burning. The froth that forms as the mixture cooks is caused by excess water, and the soap must be heated until this is evaporated. Continue to heat and add more lye until all the fat is saponified. Beat the froth with the paddle and when it ceases to rise, the soap falls lower in the kettle and takes on a darker colour. White bubbles appear on the surface, making a peculiar sound (the soap is "talking"). The thick liquid then becomes turbid and falls from the paddle with a shining lustre. Further lye should then be added at regular intervals until the liquid becomes a uniformly clear slime. The soap is fully saponified when it is thick and creamy, with a slightly slimy texture. After cooling, it does not harden and is ready to use.

To test whether the soap is properly made, put a few drops from the middle of the kettle onto a plate to cool. If it remains clear when cool it is ready. However, if there is not enough lye the drop of soap is weak and grey. If the deficiency is not so great, there may be a grey margin around the outside of the drop. If too much lye has been added, a grey skin will spread over the whole drop. It will not be sticky, but can be slid along the plate while wet. In this case the soap is overdone and more fat must be added.

Hard soap

The method for making hard soap is similar to that for making soft soap by the boiling process, but with additional steps to separate water, glycerine, excess alkali and other impurities from the soap. The method requires three kettles: two small kettles to hold the lye and the fat, and one large enough to contain both ingredients without boiling over.

Put the clean fat in a small kettle with enough water or weak lye to prevent burning, and raise the temperature to boiling. Put the diluted lye in the other small kettle and heat it to boiling. Heat the large kettle, and ladle in about one quarter of the melted fat. Add an equal amount of the hot lye, stirring the mixture constantly. Continue this way, with one person ladling and another stirring, until about two-thirds of the fat and lye have been thoroughly mixed together. At this stage the mixture should be uniform with the consistency of cream. A few drops cooled on a glass plate should show neither separate globules of oil or water droplets. Continue boiling and add the remainder of the fat and lye alternately, taking care that there is no excess lye at the end of the process. Boiled hard soaps have saponified when the mixture is thick and ropy and slides off the paddle.

Up to this point, the process is similar to boiling soft soap, but the important difference in making hard soap is the addition of salt at this point. This is the means by which the creamy emulsion of oils and lye is broken up. The salt has a stronger affinity for water than it has for soap, and it therefore takes the water and causes the soap to separate. The soap then rises to the surface of the lye in curdy granules. The spent lye contains glycerine, salt and other impurities, but no fat or alkali. Pour the honey-thick mixture into soap moulds or shallow wooden boxes, over which loose pieces of cloth have been placed to stop the soap from sticking. Alternatively, the soap may be poured into a tub which has been soaked overnight in water, to cool and solidify. Do not use an aluminium container because the soap will corrode it. Cover the moulds or tub with sacks to keep the heat in, and let it set for 2 - 3 days.

When cold the soap may be cut into smaller bars with a smooth, hard cord or a fine wire. It is possible to use a knife, but care is needed because it chips the soap. Stack the bars loosely on slatted wooden shelves in a cool, dry place and leave them for at least 3 weeks to season and become thoroughly dry and hard.

Be careful! Uncured or 'green' soap is almost as caustic as lye. Wear rubber gloves when handling the hardened soap until it has been cured for a few weeks.

Problems in soapmaking

Problems that can occur in soapmaking and their possible causes are described in Table 2.

|

Problem |

Possible causes |

|

Soap will not thicken quickly enough |

Not enough lye, too much water, temperature too low, not stirred enough or too slowly, too much unsaturated oil (e.g. sunflower or safflower). |

|

Mixture curdles while stirring |

Fat and/or lye at too high temperature, not stirred enough or too slowly. |

|

Mixture sets too quickly, while in the kettle |

Fat and lye temperatures too high. |

|

Mixture is grainy |

Fat and lye temperature too hot or too cold, not stirred enough or too slowly. |

|

Layer of oil forms on soap as it cools |

Too much fat in recipe or not enough lye. |

|

Clear liquid in soap when it is cut |

Too much lye in recipe, not stirred enough or too slowly. |

|

Soft spongy soap |

Not enough lye, too much water, or too much unsaturated oil |

|

Hard brittle soap |

Too much lye |

|

Soap smells rancid |

Poor quality fat, too much fat or not enough lye. |

|

Air bubbles in soap |

Stirred too long |

|

Mottled soap |

Not stirred enough or too slowly or temperature fluctuations during curing. |

|

Soap separates in mould, greasy surface layer on soap |

Not enough lye, not boiled for long enough, not stirred enough or too slowly |

|

White powder on cured soap |

Hard water, lye not dissolved properly, reaction with air. |

|

Warped bars |

Drying conditions variable. |

Table 2: Problems in soapmaking

(Adapted from website http://www.colebrothers.com/soap in list of further information below)

To improve hard soap

A better quality soap may be made by re-melting the product of the first boiling and adding more fats or oils and lye as needed, then boil the whole until saponification is complete. The time required for this final step will depend on the strength of the lye, but 2 - 4 hours' boiling is usually necessary. If pure grained fat and good quality white lye are used, the resulting product will be a pure, hard white soap that is suitable for all household purposes. Dyes, essences or essential oils can be added to the soap at the end of the boiling to colour it or to mask the 'fatty lye' smell and give a pleasant odour.

Hard soap recipes

The simplest and cheapest type of soap is plain laundry soap, but a few inexpensive ingredients can be used to soften the water or to perfume the product and create fine toilet soaps too. The following recipes are a few examples of easily made soaps. There are many more recipes in the information sources given at the end of this Technical Brief.

Simple kitchen soap

Dissolve 1 can of commercial lye in 5 cups cold water and allow it to cool. Meanwhile mix 2 tablespoons each of powdered borax and liquid ammonia in _ cup water. Melt 3 kg fat, strain it and allow it to cool to body temperature. Pour the warm fat into the lye water and while beating the mixture, gradually add the borax and ammonia mixture. Stir for about 10 -15 minutes until an emulsion is formed, and pour the mixture into a mould to cool.

Boiled hard white soap

Dissolve 0.5 kg potash lye in 5 litres of cold water. Let mixture stand overnight, then pour the clear liquid into a second 5 litres of hot water and bring it to a boil. Pour in 2 kg of hot melted fat in a thin stream, stirring constantly until an emulsion is formed. Simmer for 4 - 6 hours with regular stirring, and then add 5 litres of hot water in which 1 cup of salt is dissolved. Test to ensure that the mixture is saponified by lifting it on a cold knife blade, to ensure that it is ropy and clear. or

Dissolve 0.5 kg potash in 2 litres of cold water. Heat and add 2.5 kg melted fat, stirring constantly. Let the mixture stand for 24 hours and add 5 litres boiling water. Place it on a low heat and boil with constant stirring until it is saponified.

Labour-saving soap

Dissolve 0.5 kg soda lye and 1 kg yellow bar soap cut into thin slices in 12 litres of water. Boil for 2 hours and then strain. Clothes soaked overnight in a solution of this soap need no rubbing. Merely rinse them out and they will be clean and white.

English bar soap

Use 5 litres of soft water, 0.5 kg of ground (or agricultural) lime, 1.75 kg soda lye, 30g borax, 1 kg tallow, 0.7 kg pulverised rosin and 14g beeswax. First bring the water to a boil, and then gradually add the lime and soda, stirring vigorously. Add the borax, boil and stir until it is dissolved. Pour in the melted tallow in a thin stream, stirring constantly. Add the rosin and beeswax, and boil and stir until it thickens. Cool in moulds.

Transparent soap

Any good quality white soap may be made transparent by reducing it to shavings, adding one part alcohol to 2 parts soap, and leaving the mixture in a warm place until the soap is dissolved. It may be perfumed as desired.

or

Shave 0.6 kg good quality hard yellow soap and add 0.5 litres of alcohol. Simmer it in a double boiler over a low heat until it is dissolved. Remove from the heat and add 30g of essence to give a pleasant smell.

Bouquet soap

Shave 14 kg tallow soap and melt it in 2 cups water. When it is cool, add 14g essence of bergamot, 30g each of oils of cloves, sassafras and thyme. Pour it into moulds.

Cinnamon soap

Shave 23 kg tallow soap and melt it over a low heat in 1.2 litres water. Cool and add 200g oil of cinnamon and 30g each of essences of sassafras and bergamot. Mix and add 0.5 kg finely powdered yellow ochre. Mix well and pour into moulds.

Citron soap

Mix 180g shaved soap with 300g attar of citron, 15g lemon oil, 120g attar of bergamot and 60g attar of lemon.

Medicated soaps

Camphor soap

Dissolve 0.5 kg hard white soap in 1 cup boiling water. Continue boiling over a low heat until the soap is the consistency of butter. Add 180g olive oil, mixed with 30g camphorated oil. Remove it from the heat and beat until an emulsion forms. This soap can be used to clean cuts and scratches.

Sulphur soap

Shave 60g soft soap and add 8g Flowers of Sulphur. Perfume and colour may be added as desired. Mix the ingredients thoroughly in earthenware bowl.

Iodine soap

Dissolve 0.5 kg white, finely shaved soap in 90g distilled water or rose water. Add 30g tincture of iodine. Put in double boiler, melt and mix by stirring.

More recipes for soft-soap cold process

Mix 4 kg of melted fat with 16 litres of strong lye water in a kettle. Bring it to the boil, pour into the soap barrel and thin it with weak lye water. Place the barrel in a warm place. The soap should be ready to use in a few weeks.

or

Mix 5 kg clear melted fat, 3 kg soda lye and 40 litres of hot water in the soap barrel. Stir once a day and let the mixture stand until completely saponified.

or

Melt 4 kg fat in a kettle and bring it to the boil. In another kettle, mix 4 kg caustic soda and 0.5 kg soda in 20 litres of soft water. Pour all the ingredients together into a 200 litre barrel and fill it up with soft water. Stir daily for 3 days and then let the mixture stand until saponified.

or

Mix 3 kg potash, 2 kg lard and 0.2 kg powdered rosin and allow the mixture to stand for one week. Then melt it in a kettle with 10 - 15 litres of water. Pour the mixture into a 50 litre barrel and fill with soft water. Stir two or three times a day for two weeks.

or

Put 0.3 kg soda and 0.5 kg brown soap shavings into a kettle. Add 12 litres of cold water, melt over low heat and stir until dissolved. It is ready for use as soon as it is cool.

Glossary

|

• Lye, Lye water, potash lye ashes |

interchangeable terms for alkali made from wood soaked in water |

|

• Potash (caustic potash) |

lye water evaporated to a powder. |

|

• Lime (or stone lime) |

ground or agricultural limestone. |

|

• Quicklime |

lime that has been baked. |

|

• Quicklime |

lime that has been baked. |

|

• saponification |

the name given to the chemical reaction in which lye and fat are converted into one substance: soap |

|

• Soda |

hydrated sodium carbonate. |

|

• Caustic soda |

soda lye evaporated to a powder. |

|

• Commercial lye |

usually caustic soda and is the equivalent of 'lye' in most recipes. |

Equipment list

The following equipment is needed to make soap:

1. a large iron soap kettle for making soap in commercial quantities.

2. a long-handled wooden ladle to stir the soap.

3. a kitchen grater or a meat grinder to make soap flakes for laundry use or to grind soap for some recipes.

4. flat wooden boxes, moulds or tubes, cut plastic bottles or plastic tubs, to mould the soap.

5. pieces of cloth to stop the soap sticking to the wooden moulds.

6. a plate on which to cool and test a few drops of the liquid soap.

Difficulties

The ingredients needed to make soap are dangerous. Read carefully the warnings. Wear protection clothes and a face shield. Keep children away.

Success Story

Plans, Illustrations, Posters

Contacts

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail:practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk web:www.practicalaction.org

Technology Consultancy Centre, University of Science & Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. Fax: + 233 5160137

Links

For producers who can obtain assistance from a small business advisory service or an international development agency that has access to the Internet, there are 100+ websites on soap making. Most are either commercial sites that sell essences, oils etc that can be added to soap, or home soapmakers sites that give recipes and information on how to make soaps. The following websites have useful information and good links to other sites:

|

contains details of products such as essential oils and plant extracts for use in soaps, soap moulds, dyes and packaging. | |

|

has details of 'Soap Tracer' software that can be purchased to create soap recipes and calculate the amounts of oil and lye required. Also details of ingredients and equipment for soapmaking. | |

|

has a variety of free information, including recipes, safety considerations, ingredient suppliers, soapmaking methods and the properties of soapmaking oils, with links to many other soapmaking websites. | |

|

has a history of soapmaking and a free table to calculate the ratio of fat/lye for different fats and oils. There are also recipes for cold process soap and details of ingredient suppliers. | |

|

has recipes, soapmaking instructions, a fragrance calculator and saponification chart. |

Other websites that contain details of recipes and suppliers include:

http://www.alcasoft.com/soapfact

http://www.sweetcakes.com (comprehensive list of essences and essential oils for soaps)

http://www.soapcrafters.com

http://www.ziggurat.org/soap

http://www.soapmaker.com

http://www.snowdriftfarm.com

http://www.rainbowmeadow.com

http://www.wholesalesuppliesplus.com

http://www.hollyhobby.com

References and further reading

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Soap Making.

To look at the original document follow this link: http://practicalaction.org/practicalanswers/

- Small-scale Soapmaking: A handbook, by Peter Donker, IT Publishing/TCC, 1993.

- Soap Production - Technologies Series Guide No 3, Centre for the Development of Enterprise, Brussels, 1994.

- Case Study No 3: Soap Pilot Plant, Technology Consultancy Centre, Kumasi, Ghana, 1983.

- Soap, Ann Bramson, Workman Publishing Co, 1975

- The Art of Soap Making, Merilyn Mohr, Camden House Publishing, 1979

- Making Soaps and Candles, Phyllis Hobson, Storey Communications Inc., 1973

Related articles

- What to Do with Ashes

- How to Make Soap

- How to Use Chillies as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Use Garlic as a Natural Pesticide

- How to Grow Shea Trees (Karité, Nku, Bambuk Butter tree)

- How to Recycle Oil

- What to Do in Case of Cholera Epidemy

- Simple Hygien Measures for Animal and Human Health

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Categories

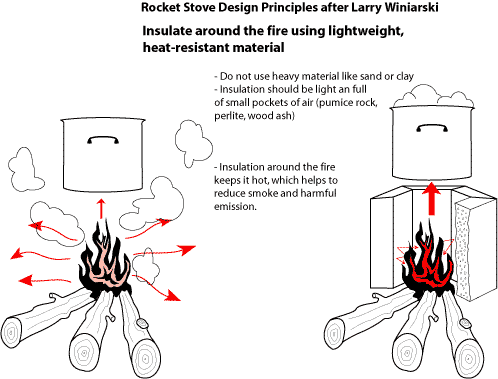

How to Build a Winiarski Rocket Stove

Short Description

- Problem: Inefficiency of Wood Stoves, Wood Shortage

- Idea: Insulating the Stove and Directing Heat Around the Pot

- Material Needed: A big bin can, Ashes or heat resistant insulating material, a tool to cut thin metal sheets

- How Long does it take? Up to one day

Description

Due to increasing wood shortage in many regions of the world, it is necessary to improve the normal open fire cooking, and most of the stoves. The heat produced by an open fire or by a normal stove is mostly lost in the air or in the materials that make the stove. This stove design proposes to insulate the combusting chamber and to direct the heat of the fire on to the cooking pot. It can be made this way:

- a big tin can which will become the combustion chamber. It has a hole on top, where the pot will come, and one on the side for the fuel magazine.

- a fuel magazine made of a sheet of metal bent into a tube, connected to the lower part of the combustion chamber. It should be quite narrow and relatively long, to encourage the user to cut the wood into long sticks that burn more efficiently

- a grid laying in the middle of the fuel magazine will support the wood sticks and let air warm up before it comes to the combustion chamber

- Once you have connected the two parts of this "elbow" you have to put the elbow in a bigger can, recipient, and fill in the distance between the elbow and the outside recipient with insulation material like wood ashes or perlite.

- You will put your pots on the top of the chimney, be sure they can be stable.

- an important part for the efficiency of the stove is the "skirt": It is a piece of metal sheet that fits 2 cm apart from your pots sides, to force the heat along the sides instead of vanishing in the air.

- If you want to cook even more efficiently, read the Haybox technique where one lets the food cooking in an insulated box after the first boil.

Important

Success Story

Models of the Winiarski Rocket Stove has been built successfully the last 13 years in more than 20 countries

Plans and Illustrations

Contacts

Aprovecho Research Center, USA, 001(541)942-8198, apro@efn.org

Links

http://www.aprovecho.net/at/projects/Design%20Principles.pdf

Link to Fourthway's poster "How to make a fuel saving stove": http://www.fourthway.co.uk/posters/pages/fuelsavingstove.html

http://www.efn.org/~apro/AT/atrocketpage.html

http://www.repp.org/discussiongroups/resources/stoves/#Dean_Still

Bibliography

- Design Principles for Wood Burning Cook Stoves, Aprovecho Research Center, Partnership for Clean Indoor Air, Shell Foundation, June 2005 (1MB pdf)

- Instructions for Building a VITA Stove by Samuel F. Baldwin, 1987, Dean Still May 2005

- Biomass Stoves: Engineering Design, Development, and Dissemination (1986) Samuel F Baldwin, VITA ISBN 0866192743

- Cookstove Efficiency Report, Dale Andreatta, January 2005

- Improved Solid Biomass Burning Cookstoves: A Development Manual RWEDP

- Cooking Stove Improvements: Design for Remote High Altitude Areas Dolpa Region Nepal, Sjoerd Nienhuys April 2005

- Improved Biomass Cookstove Programmes: Fundamental Criteria for Success.(pdf) MA Rural Development Dissertation. August 1999. Jonathan Rouse

- Measuring Cookstove Fuel Economy FAO Forestry for Local Community Development Programme Appendix II

- Village Earth Library: Improved Cookstoves and Charcoal Production

Related articles

- How to Make a Cooking Box (Hay Box / Hay bag)

- How to Use Sun Power

- How to Build an Efficient Wood Oven

- How to Build a Winiarski Rocket Stove

- How to Build Solar Cookers

- How to Build the ARTI Compact Biogas Digestor

- How to Build the Vacvina Biogas Digestor

- Biomass (Technical Brief)

- Kerosene and Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG)

- How to Build a Clean Dung-Burning Stove

Two ways to support the work of howtopedia for more practical articles on simple technologies:

Support us financially or,

Testimonials on how you use howtopedia are just as precious: So write us !

<paypal />

Categories

- Pages with broken file links

- Ashes

- Oil

- Global

- One Person

- Household

- Less than 10 US$

- Dangerous

- Hygiene

- Small Business

- Howtopedia requested images

- Health

- Ideas

- Prevention

- Products

- Recycling

- Vetiver

- One Person and more

- Application

- Practical Action Update

- Requested translation to Spanish

- Requested translation to Hindi

- Requested translation to Portuguese

- Stub

- Wood

- Energy

- Cooking

- Food Processing

- Global Technology

- Requested translation to French